Fly Phishing

PHISHING SCHOOL

How to Bypass SPAM Filters

If you have ever written the word “click” in a phishing email, then trust me; You need my help.

Be honest with me.

Have you ever written the word “click”, or “upgrade”, or “w-2” in the body of a phishing email?

If so, you have committed a cardinal sin in the phishing world, and it’s time to repent. I’m not here to judge you. We all have fallen short at one time or another. I’m here to show you a better way.

How SPAM Filters Work

Once we convince the mail server that our domain is trustworthy enough to send emails to users the next opportunity the secure email gateway (SEG) has to recognize a phish is based on the content of the message. We will have to find some way to bypass this content check if we are ever going to deliver our emails to our targets.

“The Achilles heel of the spammers is their message. They can circumvent any other barrier you set up. They have so far, at least. But they have to deliver their message, whatever it is. If we can write software that recognizes their messages, there is no way they can get around that.” — Paul Graham, 2002

As much as I respect Mr. Graham and his ideas, I think that time has proven him wrong on this particular viewpoint. It’s been a dozen years since this claim that content is the Achilles heel of SPAM and yet some SPAM and phishing emails still slip through even the most sophisticated SEGs. The task of writing software to recognize fraudulent emails has turned out to be a lot harder than it looks at first glance.

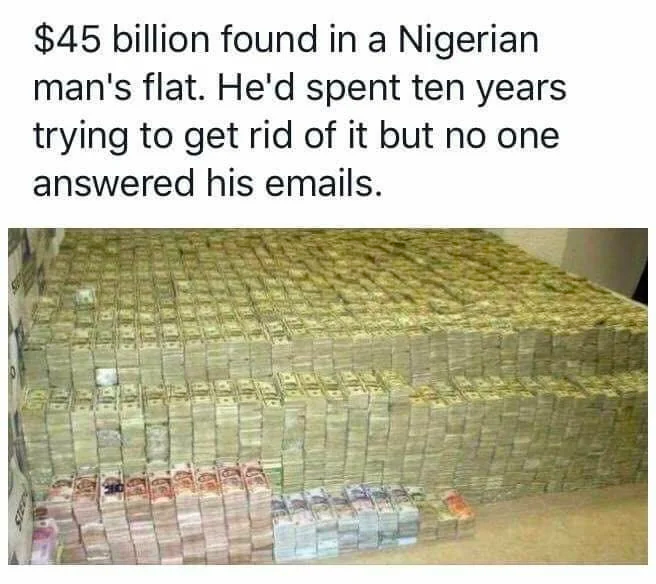

Most SEGs work in a similar way as early anti-virus software. They look for known bad words, phrases, sentences, and even whole emails and block content that has a high ‘SPAM score’. A SPAM score is a general measurement of how SPAMy a message looks. For instance, if you use a potentially bad word like ‘Nigerian’, your content will take a hit in the form of additional SPAM score points. This may not mean your message is blocked outright, but it’s now on thin ice. If you then use the word ‘prince’ in the same message, your SPAM score jumps to an unacceptable level and your message is blocked.

There are more advanced SEGs that leverage AI to analyze message content and sort messages into ‘normal’ and ‘fraudulent’ buckets, but the general principle is still the same. These models can only be trained on known phishing emails, and therefore can only be trained on messages that are obviously fraudulent to a human. These filters do a great job of identifying generic SPAM, but there is still plenty of gray area to play in that would actually fool many humans. We just need to avoid SPAM cliches and we should be just fine 🙂

Now that we know that content filters are just over-hyped word counters, let’s look at some general bypass strategies.

Use Existing/Real Emails

One of my favorite tricks for bypassing content filters is to simply copy legitimate emails that have hit my inbox in the past. If you’ve ever received a legitimate message that made you pause and think about whether it was real or a phish, then you have a prime candidate. I tend to stash these emails away in a special ‘phishing ideas’ folder for when I need a quick campaign. If a message bypasses your company’s SEG, it will likely bypass your target’s. Just capture the message content with a tool like Phishmonger, tweak the pretext, and swap out the link.

Target Specific Users

In general, you are going to have a much higher success rate bypassing content filters when you avoid generic mass pretexts. While you really just need to avoid the super cliche overdone pretexts, I find it easiest to avoid common pretexts when I am crafting more individualized messages. Keep a personal tone and make the request very specific. These types of messages tend to blend in with normal email conversations and lack the obvious cues that might cause a SEG to categorize them as phishing.

Watch your Language

Because email content filters are relying solely on the words of the message to make a determination about the SPAMiness of a message, they tend to place a high weight on a few individual words that are common for SPAM and phishing pretexts. These ‘dirty’ words include some things you might expect on a dirty word list like ‘sex’, ‘viagra’, and ‘porn’. In addition, mail filters also tend to include other words like ‘urgent’, ‘free’, ‘Microsoft’, ‘install’, ‘W-2’, ‘Outlook’, ‘click’, ‘patch’, ‘account’, and ‘upgrade’ on the dirty list as well. Some of these, like any blue pill references, will likely land an email in the SPAM bucket immediately. Others, like ‘patch’ might depend on additional context, or may just cause a generally high SPAM score without necessarily pushing it over the acceptable limit. Obviously, if we are going to deliver our phishing pretexts, we will want to avoid or otherwise obfuscate our use of any dirty words. Here’s a few dirty tricks that can help:

Don’t Say “Click”

Here’s another excellent Paul Graham quote from his 2002 essay on SPAM:

A few simple rules will take a big bite out of your incoming spam. Merely looking for the word “click” will catch 79.7% of the emails in my spam corpus, with only 1.2% false positives.

Full essay: https://paulgraham.com/spam.html

I know that you really want your targets to click your link, but you will need to refrain from seeming too eager, or else they won’t get to read your email in the first place. Mr. Graham did a bunch of fancy manual statistical analysis to find that “click” was one of the spammiest words, but I’m sure today’s machine learning algorithms are picking up on the same trend. Don’t say it!

Use Vague Substitutes

Often, you can simply avoid the dirty words altogether by being creative with our phrasing. Instead of saying something like “you will need to install an upgrade to your system”, you could say “you may need to accept some changes with your computer”. The words “accept” and “changes” tend to come up far more often, and under many more varying contexts than the words “install” and “upgrade”, which tend to only be in reference to running software. Yes, your message will be more vague, but the human target will be able to infer what you mean. It is this vagueness that will make it far more difficult for a computer to spot the underlying meaning.

Use Character Substitutions

On more than one occasion, I have had messages blocked by content filters because I used too many instances of words like ‘Outlook’, but by making the simple substitution of a zero in place of capital ‘o’, (e.g. ‘0utlook’) the messages were then allowed through. The same technique can be applied to other character groups like ‘I’,’L’, and ‘1’ by playing with the casing and using sans-serif fonts to reduce visual context that might help a human properly distinguish which is which. You could also play around with lookalike Unicode characters if you want to get fancy (thanks Will Schroeder for the suggestion!). You might just have to specify the character set in the ‘Content-Type’ header. It’s a simple trick, but can be extremely effective because the words ‘look’ completely different to the computer but not the end reader.

Other Insertions and Substitutions

Most mail clients tend to prefer displaying a rendered HTML version of an email if an HTML section is available. Therefore, we can use a little HTML trickery to create other scenarios where the rendered result looks the same to a human, but the underlying message content is different. For instance, HTML ‘span’ tags can be used in emails, but don’t actually have any visual effect on the rendered message. In some cases, we can use span tags to break up dirty words by literally shoving a span tag in the middle of the word. Some SEGs will not be able to tell that it is still a single word and may not flag it. You can also use CSS to add entire words or even sections of content that will be processed by the SEG but never visible to the end reader. This can be useful for breaking up potentially cliche or phishy phrases. You can also get creative with using images for substitutions. This can be done to substitute individual letters, whole words, or even the entire message body.

Play with Encodings

SMTP is a purely text-based protocol. However, because emails sometimes need to contain special characters (e.g. accent marks) and arbitrary binary content (e.g. attached images), there are multiple ways to encode email data. In normal use, encoding schemes like “Quoted-Printable” (QP) are only applied to special characters that require them. However, there is no technical limitation preventing you from using QP to encode every character in a message, or even encode only a portion of a word. While the end message will look exactly the same to our human targets when rendered by the mail client, the message will look very different to a computer while in transit. In some cases, we can use this to our advantage to break up ‘dirty’ words that we know might increase our SPAM score.

Pro Tip: Quoted-Printable is only one of several ways you can encode email data. There are several more absolute gems hiding in the specs that define the SMTP protocol. A great place to start for purposes of this discussion would be rfc2045 https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc2045. It’s actually a short read and not super technical. I repeat! SMTP is a text-based protocol! This stuff was just written in plain English back in 1996. Do yourself a favor and take an interactive tour of some Internet history that holds up the foundation of modern corporate communication.

Weighing Your Phish

Or rather, “weighting” your phish with benign content can help with bypassing AI-based content filters. With language learning models in the mainstream these days, most decent SEGs use some form of AI based detections, and many of the top SEGs rely almost exclusively on AI as email gatekeepers. As a result, some common and well known attacks against AI models can be very effective at bypassing modern email filters. One simple but effective attack is simply to add ‘known good’ content to a message to increase its overall ‘goodness’. Rather than over-explain the technique, I think a couple examples are more useful in this case:

Case 1: Bypassing Cylance’s AI

In 2019, some researchers found a categorical bypass for Cylance’s AI-based threat detection engine and released an excellent blog detailing the bypass called “Cylance I Kill You”. They found that one popular game called Rocket League used a lot of hacky memory manipulation techniques that are commonly also abused by malware, but that Cylance would allow this particular game to run without issue. While the use of these memory ‘optimizations’ would look very much like malware to many security products, it seemed Cylance’s AI model had been trained to ignore these warning signs in the case of this very popular game. The researchers then found that by simply adding a bunch of strings, found in the Rocket League binary, to any malware sample, they could achieve a detection bypass of “100% of the top 10 Malware for May 2019, and close to 90% for a larger sample of 384 malware.” according to their article.

Case 2: Bypassing O365 AI

A few years back, circa 2020, I was struggling to deliver phishing emails to a target organization that was using Office365’s email filter. At the time, my employer was also using O365 for email filtering and I was already in the habit of collecting odd and sketchy looking emails that hit my inbox as potential templates to run against other SEGs. I had recently heard about the Cylance AI bypass and wanted to know if the same technique would work against email filters.

One “legitimate” email that had recently crossed my inbox that I thought was particularly interesting was a mass phishing… oops I mean “marketing” campaign from Adobe Pro. The email looked about as SPAMy as possible to me, but somehow O365 had let it directly through to my inbox. It seemed that either the Adobe marketing team had found the secret sauce to bypass O365’s filter with just the right wording, or that they skipped the hard part and just paid Microsoft to let it through. In either case, the O365 model was trained to believe that no matter how SPAMy it looked, the Adobe Pro message was definitely not SPAM. As a test, I copied the footer from the “legitimate” Adobe message and appended it to my previously blocked content. To my jaw-dropping surprise, the messages finally got through… every time! I added a bunch of carriage returns just before the footer to make sure that end users never saw the additional content and shared this template with co-workers who used it for several months as a categorical bypass when facing O365.

Fly Phishing: Both a Craft and a Sport

Yes, any old lure might do, but a well crafted lure will do much better! Embrace the idea that you are in control of every intricate detail of your message, and use that to your advantage. Be crafty. Be skillful. When done well, you should have a sense of pride in the little masterpieces you conjure up.

Here’s just a few tricks from the old tackle box…

Don’t Miss Easy Wins

In the last blog, we covered a few easy wins to bypass SPF. When it comes to content filtering there is one main bypass that you should be aware of and look for: whenever possible, don’t traverse the filter! There are two pretty common scenarios that I’ve seen that might allow you to completely bypass a content filter. The first is when your target organization hosts their own mail server, with port 25 open, but does not host their own content filter for this server. Usually, when I’ve seen this at a client, it is an old on-prem mail server that they used before moving to a cloud email provider, but has not been decommissioned yet. Similarly, I have also seen multiple cases of on-prem SPAM filters that have port 25 open to the Internet, and have the ability to deliver mail to end users, but are out-of-date on their license and therefore completely useless at blocking malicious emails.

The other common bypass I’ve seen is organizations that use a mail provider like Office365 and automatically have a tenant mail server set up, but don’t publish the “targetdomain-com.mail.protection.outlook.com” endpoint to their MX records. By default, this email gateway will be set up for “targetdomain.com” and allow inbound messages from any source. Organizations that utilize O365 for email services, but some other provider for content filtering should ensure that their O365 gateway only accepts messages from the content filter provider, otherwise we can completely bypass the content filter and send directly to the O365 gateway instead.

Use a Real Mail Client and Server

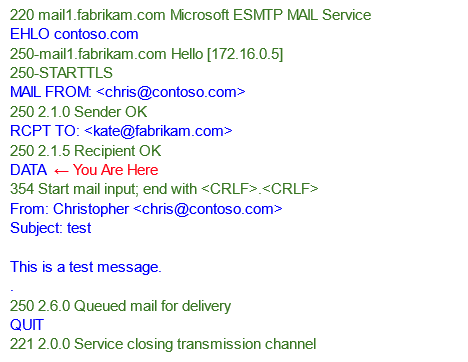

The tools we use to phish can often add dead giveaways to our message content without our knowledge. Have you ever sent yourself an email with Gophish, SET, Phishing Frenzy, etc. and compared the ‘source’ to a real email? One thing you’ll notice right away is that the email structure is very different. There will be a lot of common headers missing, the section and content nesting will not look like a real email, and the content delimiters will look funky and generally look similar based on the phishing tool used. The problem is that these common phishing frameworks simply leverage common open-source SMTP libraries to meet the minimum requirements to form a syntactically correct message. In contrast, legitimate emails are crafted by users in their mail clients, which are very feature rich, complex, and generate very different looking SMTP data.

To make our messages look as legitimate as possible, the best approach is to simply craft our messages in a mail client and then copy out the source. To do this manually, you would craft your phishing message in Outlook or similar, send it to yourself, click ‘view source’, and copy out the content. However, this approach will not work well if you want to use popular frameworks like Gophish. You can copy out the HTML content of the message, but you will still be at the mercy of the phishing tool’s default settings for other message elements like alternate content, content nesting, headers, and content delimiters. It’s for this reason that I decided to write Phishmonger.

https://github.com/fkasler/phishmonger

Phishmonger is a phishing framework that allows you to both send AND receive emails just like a real mail server. The biggest benefit of this approach is that we can craft phishing emails in a mail client, and send them to your Phishmonger server to capture the raw content of the SMTP DATA section. You can then send out the exact same content, with only minor substitutions for things like per-target phishing links, and you will guarantee that the message will look the same when it hits the target’s inbox as when you crafted it in Outlook. And, of course, the message content will ‘look’ like it originated from a real mail client, because it did.

Building Confidence

I hope the previous sections have opened your eyes to just how many ways we can manipulate content to potentially slip past content filters. Though I can already anticipate one big complaint from my readers…

Question: “All this theory about content filter bypasses is great to talk about, but I’m still up against a complete black box when I try to apply these techniques against a SEG on a real campaign. How do I know what’s going to work?”

Answer: You are (almost) correct. Yes, SEGs are black boxes. That is, UNTIL we test them!

If you want to build confidence that your content filter bypass is going to work, you will need to test a range of bypass techniques against the SEG used by your target organization. Given that most SEGs are cloud-based SAAS providers, and most customers leave the majority of settings in their default state, you can be reasonably assured that if you can bypass the filter in a test environment, that you will likely be successful using the same pretext against your target. To do this, our options are either to register a test account with the SEG provider, or to use bounce messages to infer spam scores using misconfigured SEGs that we can find on the internet.

But First… What SEG is my Target Using?

Again, most popular SEGs utilize a SAAS business model to protect their secret sauce. This means that you actually send emails to servers owned by the SEG provider. This means that their clients must set an MX record that points to a SEG asset. In most cases, they instruct clients to set an FQDN for this record and the top level clearly indicates the SEG provider. In more rare cases, they instruct clients to set an IP as the MX record, but we can often use either the WHOIS record for the IP or the ASN to determine which SEG owns the IP. In VERY rare cases these days, you might find a target org that hosts an on-prem SPAM filter appliance. In these cases, your best bet might be to just call some employees and social engineer them to see if any know what the spam filter is.

Setting Goals

Before we talk about SEG testing, I think it makes sense to define an objective to give us some direction. For instance, if we use a trial account for testing, we will only have a limited window of time to run tests before we have to pay for the service. How should we maximize our time?

A naive approach would be to simply test the pretext that we are about to send to our current target organization and make tweaks to the content until it slips through.

A slightly better approach might be to come up with a big list of pretexts and alternative wordings that you might want to send, and see which ones get through and which ones get blocked.

An even better approach is to come up with lots of potential bypass techniques, and attempt to find a categorical bypass for the target SEG. This is typically my end goal when testing a given SEG. I will send a variety of intentionally SPAMy messages, to make sure they are blocked by the filter, and then apply iterations of potential bypasses and obfuscations to see if I can force an arbitrary ‘bad’ message to slip through anyway. If I’m successful, it means I can use the same bypass technique to deliver messages against the same SEG for some amount of time with a relatively high confidence interval of success.

If you wanted to take this approach even further, you could also use your trial account to quickly test hundreds or even thousands of test messages and collect telemetry on which emails made it through to build an AI model that mimics the target SEG. In many cases, SEGs apply an SMTP header that contains the calculated SPAM score of each message. In these cases, it is possible to build an AI model that is a very close approximation of the model used by the target SEG. Back in 2019, Will Pearce and Nick Landers demonstrated an attack against Proofpoint using this technique:

https://github.com/moohax/Proof-Pudding

You can then apply potential obfuscation techniques against your own model offline to rapidly prototype bypass techniques and still maintain a reasonable assurance that any discovered categorical bypasses will also work against the target SEG. If you are interested in using this technique, I would highly recommend looking at the methodologies and obfuscation techniques used by some of the MLSec competition winners from the last few years:

https://cujo.com/blog/mlsec-2022-the-winners-and-some-closing-comments/

Dev Environment Testing

The most straightforward way to test content against a particular SEG is to register a trial account. Most trials work on the basis of a trial period that is entirely time based. Therefore, it makes sense to collect as much data as possible within the trial period as possible. If you are going for categorical bypasses, you should have a list of potential message transforms ready to go before registering your test account. Ideally, you will want to leverage some obfuscation scripts to print test messages for you. This will allow you to iterate quickly and keep the bypass techniques consistent between test messages. If you are going with the AI model replication approach, you will want to make sure you have a large set of test messages ready to go and a sending script that can accommodate matching individual messages to their resulting SPAM score. In this case, you may want to do a dry run against a test mail server you set up yourself to make sure all of the moving parts are working correctly.

Crowdsourcing Bypasses

Imagine you set up a domain to look like a legitimate business. You stand up a website, some marketing content, a few social media profiles, and a mail server. You then shove fake email addresses for your fake business all over the internet on LinkedIn, Twitter, Github, WHOIS records, message boards, newsletter subscriptions, Youtube comments, etc. You should expect that pretty soon your mail server will be flooded with unsolicited emails from all sorts of untrustworthy sources. But, what if we just let all of the SPAMers think they had a successful delivery with a “250 OK” message? You might quickly have a domain that is essentially a SPAM magnet. Now, what could you do with a SPAM magnet? How about crowdsourcing bypass techniques?

SPAM and phishing is still a thing because it works. The “real” SPAMers might be annoying, but they aren’t stupid. They know that it’s worth the effort to come up with SPAM filter bypasses and often find some unique tricks to ensure their messages get delivered to end users. At a minimum, we can create a SPAM magnet domain to collect a large corpus of potentially good training data to test and identify various bypass techniques. With a thriving SPAM magnet (receiving hundreds of messages a day) we can also just swap the SPAM magnet’s MX record to automatically attack our trial SEG account and see what makes it through. Inevitably, some of these messages will bypass the target SEG and give us valuable telemetry about which messages and message features are able to defeat the SEG. It’s sort of like getting a big list of trick plays that your opponent’s defense has completely failed to stop in the recent past. You can then either completely copy the pretext of emails that you think might work against your target organization, or identify common themes in the messages that got through to apply the same styles/bypasses to your own pretexts.

Free Testing

Most SEGs will receive and process each email, assign it a SPAM score, stamp the score in an additional SMTP header on the message, and then deliver the message to their client’s mail server. Their client’s mail server then reads the SPAM score from the message’s SMTP header, along with some other metadata like the SPF pass/fail status, to determine whether to drop the message or deliver it to the end user.

In some cases, when a message cannot be delivered to the intended MAIL TO address, the mail server will send back a bounce message in a thread and include the SPAM score header from the SEG in the message source. Most SEGs don’t keep a list of valid MAIL TO addresses for their clients, and therefore will accept and process messages with any MAIL TO as long as it is for the domain of one of their customers. Therefore, we can intentionally send emails to bad addresses like “[email protected]” to coerce the SEG to assign a SPAM score to the message, forward it to mytargetorg.com’s mail server, and get a bounce back to our MAIL FROM address and potentially see the SPAM score to know whether it would have been delivered to a real mailbox. Obviously, if our target organization has a mail server configuration that exposes this type of vulnerability, it’s an extremely useful preflight check for any pretext we would like to send.

Even if your target organization is not vulnerable to leaking SPAM scores in bounce messages, we can still find other organizations that are vulnerable and utilize the same SEG and use them as a good approximation of how SPAMy the SEG thinks our message is. In 2020, Sebastian Salla published an excellent blog post, BSides presentation, and tool called Phishious for automating this technique. I would highly recommend watching his presentation and checking out the tool:

https://github.com/CanIPhish/Phishious

Warning: this technique is in a bit of a gray area. While you are not actually delivering phishing messages to any employees at the test domains, you are using their email infrastructure in a way that might be frowned upon. It’s for this reason that Sebastian intentionally avoided publishing his process for finding good target domains. Though, if you know what you’re looking for, you can pretty quickly set up an automated scanner to find useful targets.

In Summary

Modern Secure Email Gateways (SEGs) tend to rely heavily on machine learning to filter messages based on content. These models tend to automatically assign a high weight to certain words and phrases that are commonly included in phishing messages. By simply avoiding these ‘dirty’ words, we can often tweak our pretexts to slip past the filter. We can also take this process to the next level by using obfuscation techniques, paired with testing to provide a feedback loop that can help us identify categorical bypasses for our target SEG. If we find a categorical bypass, we can then have reasonable assurance that we will be able to deliver arbitrary messages to our phishing targets’ inboxes.

In the next post, we will tackle (…hehe) the next obstacle of actually convincing our target users to click on our link or open our attachment!

Fly Phishing was originally published in Posts By SpecterOps Team Members on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Posts By SpecterOps Team Members - Medium authored by Forrest Kasler. Read the original post at: https://posts.specterops.io/fly-phishing-7d4fb56ac325?source=rss----f05f8696e3cc---4