The Vectors of Language

Recall that in previous iterations we described the required steps for

our code classifier to work, which can be roughly summarized as:

Fetching data.

Representing code as vectors.

Training the classifier.

Making predictions.

Feeding new data back to the source.

It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that, out of all of these,

probably the hardest and most delicate step is representing code as

vectors. Why? Because it is the one least understood. There are numerous

helpers to handle data gathering, even at large scale. Neural networks,

or in general machine learning algorithms for classification? Done. The

infrastructure and working environment are also already there. Amazon

Sagemaker has it all. Also, as is the case with any machine learning

system, the quality of predictions will be determined by the quality of

the training data: garbage in, garbage out. Thus, we must be

particularly careful with the input we give our classifier, which will

be the output of this earlier vector representation step.

However, for the task of representing code in a way that is useful for

machine learning techniques, there is not much in the literature, except

for a couple of well-known techniques, one of which is code2vec. In

turn, this is based on word2vec, which is a model for learning vector

representations of words. To understand vector representations of code,

we must first understand the analogous for natural language, since that

might be easier to grasp and visualize because no matter how good of a

coder you are, natural language is more natural to understand.

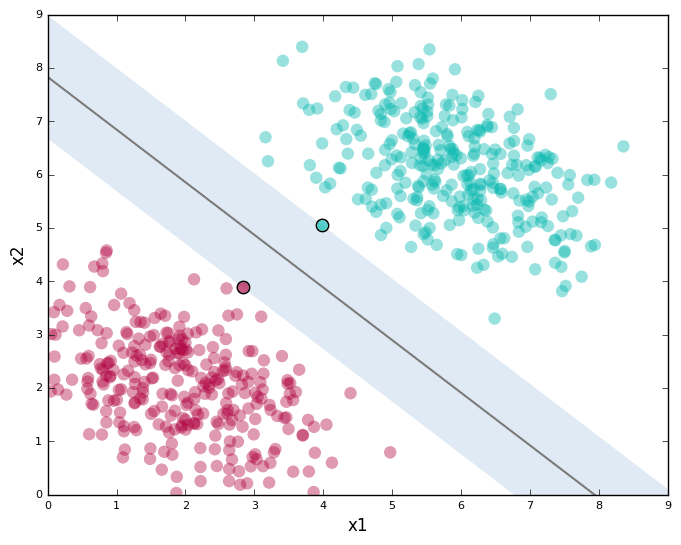

Much like code, natural language is not a good fit for machine learning

algorithms which, as we have shown here, exploit the spatial relations

of vectors in order to learn patterns from data. This is particularly

clear in methods such as Support Vector

Machines and

K-means

clustering, which

are easy to visualize when the data is two dimensional or reduced to

that.

Figure 1. Support Vector Machine example

So, we would like to have n-dimensional vector representations of words

(resp. code) such that words with similar meaning are close in the

target space and which, hopefully, show some structure in the sense that

analogies are preserved. The classic example of this is called “King –

Man + Woman = Queen” which is another way of saying that the vector from

man to woman is very similar to the one from king to queen, which makes

sense. therefore, the vector from man to king is almost parallel to the

one from woman to queen.

Figure 2. Relations between words as difference vectors,

via Aylien.

Not only can we capture male-female relations using word embeddings, but

we can capture other kind of relations such as present-past tense as

well. Notice how the difference vector between a country’s vector and

its capital’s vector is, in almost every case, a horizontal one. Of

course, what relations are caught and the quality of the results will

depend on the nature and quality of the data the model is trained with.

So, how does one go about representing language in a way that is

spatially meaningful? Perhaps the simplest way is the one we used in our

early model for classifying vulnerable code. Words are nothing but

labels for things. “Shoe” is, in the eyes of a machine, as arbitrary as

“zapato” to describe something used to cover your foot. It might as well

be called “34”, why not? Do that for every word, and you’ve got yourself

a categorical encoding. In reality, it’s not that arbitrary. You start

with a piece of text (resp. code, in all future iterations when it says

text that can be done for code; this will be discussed in an upcoming

article) called a corpus, which is what you will train on. Take as a

universe all the words occurring in the corpus, and assign numbers to

each of those from 1 to the size of the corpus. Thus, a sentence is

encoded as the vector made out of each word’s label. So, if our corpus

is “A cat is on the roof. A dog is, too’ The encoding of the first

sentence could be <1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6> and of the second, <1, 7, 3,

8>. For simple sentences of the form “A x is on y”, it’s not

unmanageable, but you can imagine that this scheme gets out of control

very fast as the corpus size increases. A related encoding is one-hot

encoding. The same labels we assigned before are now positions in an

8-dimensional vector. Thus, the first sentence is encoded as <1, 1, 1,

1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0> and the second as <1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1,

1>. We can also count repetitions here. We see several problems with

these kinds of encodings. In one-hot, the order is lost, and the vectors

would become too sparse for large corpora. A pro: all vectors are the

same size, which is not true for categorical encoding. So, we would also

like vectors that are of the same size, m for the sake of comparison,

and hopefully, which are not too high-dimensional.

A common saying is that deep learning (essentially, neural networks with

many layers) which has proved to be the most successful approach to

difficult problems such as image recognition, language translation, and

speech-to-text, is really all about representation learning. This is

exactly what we need. The thing is, these representations are usually

internal to the network, and end-users only see the results. For

example: “This is 99% a cat. But you’ll never know how I know”, or for

us, “This code is 98% likely to contain a vulnerability”. The genius

idea in Word2Vec was to make up a network for a totally unrelated

task, and ignore the results, focusing instead on the intermediate

representations created by the network in the hidden layer. By the way,

the model is a simple 3-layer network with the task of predicting either

a word from its neighbors, known as the continuous bag-of-words model,

or the opposite: given a word, predict one of its neighbors, known as

the skipgram model. Following the example above, ‘on’ should be

predicted from ‘cat is the roof’, and backwards in the skipgram model.

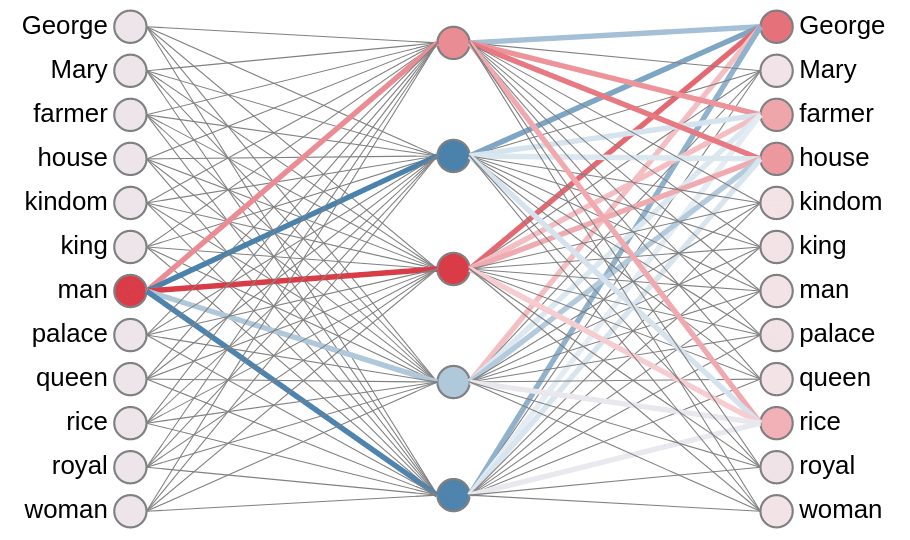

So we make up a simple 3-layered neural network, and train it on (word,

neighbor) pairs, such as (on, cat), and (on, the):

Figure 3. Example Word2Vec network, created with

wevi.

Here, we trained a network with queen-king examples to obtain the

infamous “King – Man + Woman = Queen” analogy using the

wevi tool by Xin Rong (kudos!). In

the state above, the network predicts from “man”, with highest

likelihood, “George”, which is the only man name in the set. Makes

sense. In that image, red means a higher activation level between the

neurons and blue a higher inhibition. We also obtain a visualization of

the vectors obtained from the hidden-layer intermediate representation

which is what we’re after anyway.

Figure 4. Example Word2Vec vectors, created with wevi.

There it is! In the image please ignore the orange input dots and focus

on the blue ones, which are the vector representations of the words we

came for. Notice how ‘man’ and ‘woman’ are in the first quadrant while

the titles ‘queen’ and ‘king’ are in the fourth. Other words are

clustered around the origin, probably because there is not enough

information in the training data to place them elsewhere.

While this is not yet directly related to security, Word2Vec is

nothing less than an impressive application and fortunate by-product of

neural networks applied to a natural language processing problem. What

will be certainly more interesting for our purposes is Code2Vec,

coming up next. Stay tuned!

References

- T. Mikolov, I. Sutskever, K. Chen, G. Corrado, and J. Dean.

Distributed Representations of Words and Phrases and their

Compositionality. In Proceedings of

NIPS, 2013.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Fluid Attacks RSS Feed authored by Rafael Ballestas. Read the original post at: https://fluidattacks.com/blog/vector-language/