Digression to Regression

After our risk quantification series, it should come as

no surprise that we like numbers and measuring. However, when confronted

with the question, “Why do you need to translate code into vectors?” I’m

not sure what to say.

Almost all machine learning algorithms in abstract, and the concrete

tools and libraries from the Python data science toolset (Numpy,Pandas, Keras) expect the features and targets to be real-valued.

They rely on concepts such as distance, error, and cost functions,

and they attempt to minimize the latter by adjusting their inner

parameters. All of these concepts are inherently mathematical.

Out of all of these algorithms, the easiest to understand well is

perhaps the simple linear regression. So, let’s start with that.

Regression is a fundamentally different kind of task from the ones we

have discussed the most in the

series, which are classification and

clustering tasks. Regression aims to predict a number taken from a

continuum instead of answering “yes” or “no” or to tell from which

group an input most likely belongs.

The situation is this: we have two variables that appear to be linearly

related, and we would like a model that generalizes that relationship.

Simple linear regression is used for many interesting purposes, such as

determining:

he relationship between the sales price of an asset vs. its age,

i.e., understanding depreciationthe fuel efficiency of a vehicle: fuel consumption vs. distance

coveredthe effectiveness of advertising: money spent on ads vs. revenue

indirectly measuring physical quantities, such as speed or

acceleration

In the first three examples above, it could be argued that there are

other variables at play, that the relationship might not be necessarily

linear, etc. But in the last case, and under lab-controlled conditions,

it is true that the position x of an object that moves at constant

speed v after a time t departing from an initial position i is

given by x = vt + i. Suppose we want to know the speed v using only

a ruler and a watch. If measurements were perfect, we would only need

two, for we have two unknowns: v and i. However, in reality,

measurements are not perfect, so we need to take several measurements,

and sort of “average them out” via fitting a line, i.e., the regression.

We can take several measurements of x and t, which we might register

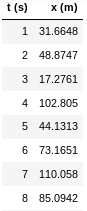

in a table like this:

Figure 1. Position vs. time, first few observations

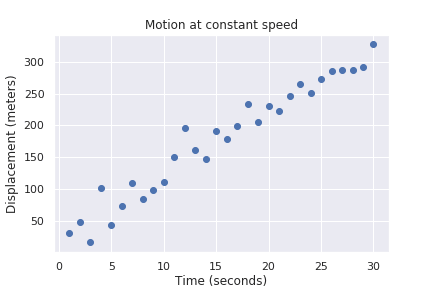

This doesn’t say as much as a plot:

Figure 2. This shows positive correlation

Here we see there is a clear linear relationship, but no single line

would perfectly fit all points. The goal in linear regression is to find

the line that best fits the points. But what is the “best” fit? There

are several choices, and each of those choices would represent a

different model. The standard in linear regression is to minimize the

sum of the squares of the errors for each observation. What? Each choice

of v and i would produce, for each value of t, a corresponding

value for x, which may be close or far from the actual observation.

The difference between these two is called a residual. But we don’t care

about each individual residual, we want only to make them small overall.

So we add them all, but before that, we square them in order to avoid

the possibility that due to the signs, they might end up adding to

something close to 0. This is, in fact, the cost function for this

particular algorithm: different techniques come with different cost

functions and different ways to minimize them.

In simple linear regression, the expression for the cost function is

easy enough to solve with pen and paper. In other algorithms,

hill-climbing and gradient descent techniques are taken from

optimization. Even simple brute force (trial and error) might be used,

as long as the cost function is minimized.

Instead of implementing simple linear regression in pure Python, which

could be done, let this serve as an excuse to present the general

machine learning flow. The tool of choice to perform “traditional”

machine learning and data analysis in Python, i.e. everything but neural

networks, will be scikit-learn. The flow to

use this library is typically the same, regardless of how sophisticated

the chosen model:

- Create an illustration of the model:

Creating a linear regressor in scikit.

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegressionmodel = LinearRegression(fit_intercept=True)- Train (fit) with the data

model.fit(t, x)Assuming that t and x are NumPy arrays (a more mathematically

appropriate extension of lists) holding the time and position variables,

respectively.

- Make predictions

import numpy as nptime = np.linspace(0, 31, 1000).reshape(-1,1)xfit = model.predict(time)Create a new array holding a thousand evenly spread values for time, and

then use the trained model to predict their corresponding values in the

independent variable.

- Assess model performance

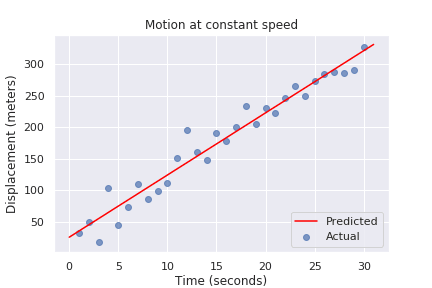

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltplt.scatter(t, x, alpha=0.7)plt.plot(time, xfit, 'red')

Figure 3. Regression line fits the data relatively well

In the case of simple linear regression, it is possible to see how

well the model performed (see above). Quantitatively, we can use the

R2 metric:

>>> model.score(t, x)0.9531426066695182The closer this value is to 1, the better the fit, and hence, the

regression.

That is, in a nutshell, how to make, train and draw predictions from

machine learning algorithms in scikit, with a few subtle changes from

one to the next, such as:

Usually, one splits the data into training, validation and testing

sets. However, the expected format remains the same. The features

or predictors (t above, but usually x) need to be an array of

vectors, and the targets or labels (usually y) a simple list

or1Darray.The validation and testing are performed in different ways according

to the task, since plotting them and getting a single evaluating

number as above is not always feasible.

Perhaps this helps to explain why you need to translate code into

vectors. More later, on why, and how to turn natural language and code

into vectors so that they might be used by standard ML techniques.

References

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Fluid Attacks RSS Feed authored by Rafael Ballestas. Read the original post at: https://fluidattacks.com/blog/digression-regression/