Crash Course in Machine Learning

In this article we clarify some of the undefined terms in our previous

article and thereby explore a selection of

machine learning algorithms and their applications to information

security.

This is not meant to be an exhaustive list of all machine learning

(ML) algorithms and techniques. We would like, however, to demistify

some obscure concepts and dethrone a few buzzwords. Hence, this article

is far from neutral.

First of all we can classify by the type of input available. If we are

trying to develop a system that can identify if the animal in a picture

is a cat or a dog, initially we need to train it with pictures of cats

or dogs. Now, do we tell the system what each picture contains? If we

do, it’s supervised learning and we say we are training the system

with labeled data. The opposite is completely unsupervised learning,

with a few levels in between, such as

-

semi-supervised learning: with partially labeled data

-

active learning: the computer has to “pay” for the labels

-

reinforcement learning: labels are given as output starts to be

produced

However, each algorithm typically fits more naturally either in the

supervised or unsupervised learning category, so we will stick to those

two.

Next, what do want to obtain from our learned sytem? The cat-dog

situation above is a typical classification problem; given a new

picture, to what category does it belong? A related but different

problem is that of clustering, which tries to divide the inputs into

groups according to the features identified in them. The difference is

that the groups are not known beforehand, so this is an unsupervised

problem.

Figure 1. Classification.

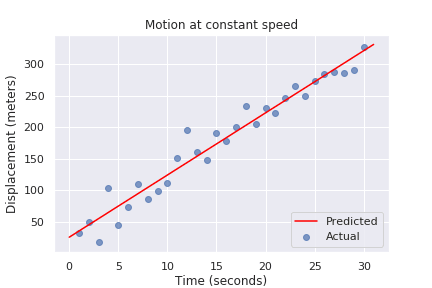

Both of these problems are discrete, in the sense that categories are

separate and there are no in-between elements (a picture that is 80% cat

and 20% dog). What if my data is continuous? Good old regression to

the rescue! Even the humble least squares linear regression we learned

in school can be thought of as a machine learning technique, since it

learns a couple of parameters from the data and can make predictions

based on those.

Figure 2. Linear Regression

Two other interesting problems are estimating the probability

distribution of a sample of points (density estimation) and finding

a lower-dimensional representation of our inputs (dimensionality

reduction):

Figure 3. Dimensionality reduction.

With these classifications out of the way, let’s go deeper into each

particular technique that is interesting for our purposes.

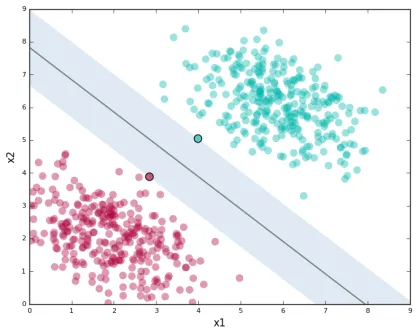

Support vector machines

Much like linear regression tries to draw a line that best joins a set

of closely correlated points, support vector machines (SVM) try to

draw a line that separates a set of naturally separated points. Since a

line divides the plane in two, any new point must be on one of the two

sides, and is thus classified as belonging to one class or the other.

Figure 4. Support Vector Machines in 2D and 3D.

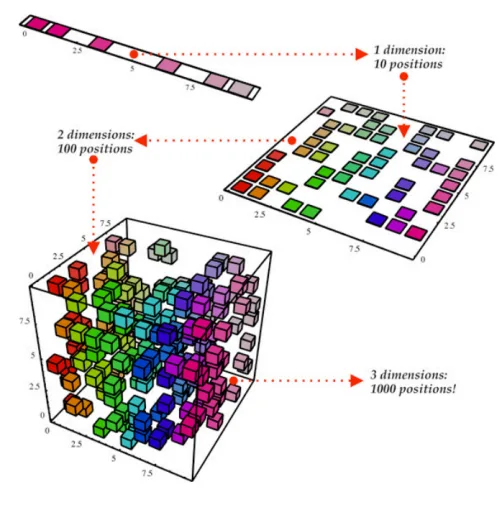

More generally, if the inputs are n-dimensional vectors, an SVM

tries to find a geometric object of dimension n-1 (a hyperplane)

that divides the given inputs into two groups. To name an application,

support vector machines are used to detect spam in images (which is

supposed to evade text spam filters) and face

detection.

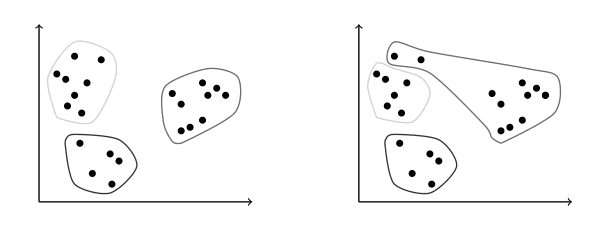

K-means clustering

We need to group unlabeled data in a meaningful way. Of course, the

number of possible clusterings is very large. In the k-means

technique, we need to specify the desired number of clusters k

beforehand. How do we choose? We need a way to measure cluster

compactness. For every cluster we can define its centroid, something

like its center of mass. Thus a measure of the compactness of a cluster

could be the sum of the member-to-centroid distances, called the

distortion:

Figure 5. Distortion is lower on the left than on the right, so compactness is better.

With that defined, we can state the problem clearly as an optimization

problem: minimize the sum of all distortions. However, this problem is

NP-complete (computationally very difficult) but good estimations can

be achieved via k-means. It can be shown and, more importantly, makes

intuitive sense, that:

-

Each point must be clustered with the nearest centroid.

-

Each centroid is at the center of its cluster.

Clustering has been used in the context of security for malware

detection; see for example Pai

(2015) and Pai et al.

(2017).

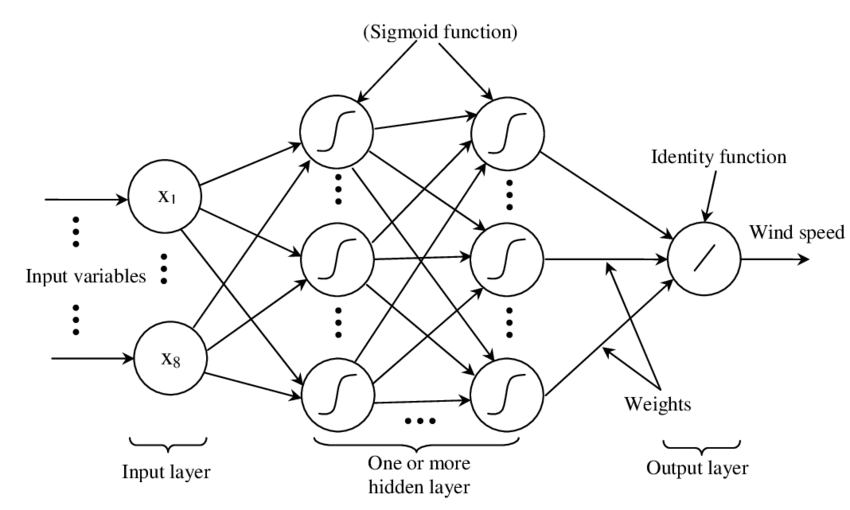

Artificial neural networks and deep learning

Loosely inspired by the massive parallelism animal brains are capable

of, these models are highly interconnected graphs in which the nodes are

(mathematical) functions and the edges have weights, which are to be

adjusted by the training. A set of weights is scored by the accuracy of

labeled output, and optimized in the next step or epoch of training in

a process called back-propagation (of error). The weights are adjusted

in such a way that the measured error decreases. The nodes are arranged

in layers and their functions are typically smooth versions of step

functions (i.e., yes/no functions, but with no big jumps), and there are

two special layers for input and output. After training, since the whole

network is fixed, it’s only a matter of giving it input and getting the

output.

Figure 6. A neural network with two layers.

The networks described above are feed-forward, but there are also

recurrent neural networks. Convolutional networks use mathematical

cross-correlation

instead of regular smooth step functions. Deep neural networks owe

their name to the great number of layers they use and to the fact that

they are unsupervised learning models.

While these networks have been quite succesful in applications, they are

not perfect:

-

in contrast to simpler machine learning models, they don’t produce

an understandable model; it’s just a black box that computes output

given input. -

biology is not necessarily the best model for engineering. In Mark

Stamp’s words [1],

Attempting to construct intelligent systems by modeling neural

interactions within the brain might one day be seen as akin to trying

to build an airplane that flaps its wings.

Decision trees and forests

In stark contrast to the unintelligible models extracted from neural

networks, decision trees are simple enough to understand at a glance:

Figure 7. A decision tree for classifying malware. Taken from [1].

However, decision trees have a tendency to overfit the training data,

i.e., are sensitive to noise and extreme values in it. Worse, a

particular testing point could be predicted differently by two trees

made with the same training data, but with, for example, the order of

features reversed.

These difficulties can be overcome by constructing many trees with

different (even possibly overlapping) subsets of the training data and

making the final conclusion by choosing from among all the trees’

decisions. This solves overfitting, but the intution obtained from

simple trees is lost.

Anomaly detection via k-nearest neighbors

Detecting anomalies is a naturallyunsupervised problem and really makes

up a whole class of algorithms and techniques, more data mining than

machine learning.

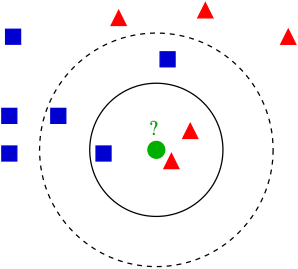

The k-nearest neighbors algorithm (kNN), essentially classifies an

element according to the k training elements closest to it.

Figure 8. The new point would be classified as a triangle

in 3NN, but as a square in 5NN.

The kNN algorithm can also be adapted to be used in the context of

regression, classification, and anomaly detection, in particular by

scoring elements in terms of the distance to its closest neighbor

(1NN).

Notice that in kNN there is no training phase. the labeled input is

the training data and the model in itself. The most natural application

for anomaly detection in computer security is in intrusion detection

systems.

I hope this article has served to establish the following general ideas

on machine learning:

-

Even though

MLhas gained a lot of momentum in the past few years,

its basic ideas are quite old. -

Fancy names can sometimes be used to masquerade simple ideas.

-

MLis not a field of its own, rather an application of statistics,

optimization, data analysis and data mining.

References

- Mark Stamp (2018). Introduction to Machine Learning with

Applications in Information Security. CRC

Press.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Fluid Attacks RSS Feed authored by Rafael Ballestas. Read the original post at: https://fluidattacks.com/blog/crash-course-machine-learning/