Gherkin on Steroids

In the field of information security, ‘finding all vulnerabilities’ is

as important as ‘reporting them as soon as possible’. For that, we need

an effective means to communicate with all stakeholders. We have

proposed before using Gherkin. In that entry, we

showed how to use `Gherkin’s syntax in order to document attack

vectors, i.e., how to find and exploit vulnerabilities in an app. We

also showed the basics of the language, so if you haven’t done so

already, we recommend you to take a look a it.

More keywords

Sometimes you need to specify a larger piece of text than fits in a

decent-length

line.

For that, Gherkin, has docstrings ("""):

Specifying long input.

When I inject the following SQL query in the input field:

"""

INSERT INTO mysql.user (user, host, password)

VALUES ('name', 'localhost', PASSWORD('pass123'))

"""

Then I have granted myself access to the database

You may write anything between the docstrings, but they must be in

their own lines and the indentation is relative to them. They are

particularly useful for citing code, output from CLI programs and

unstructured plain text.

For ‘structured’ plain text, Gherkin has the Data Table syntax

element, (don’t confuse with tables from Scenario Outlines):

Tabular data with tables.

Given the database is populated with the species:

| Common Name | Genus | Species | Family |

| Lion | Panthera | Leo | Felidae |

| GNU | Connochaetes | Gnou | Bovidae |

| Gentoo Penguin | Pygoscelis | Papua | Spheniscidae |

| Burr gherkin | Cucumis | Anguria | Cucurbitaceae |

You don’t have to align the pipes (|) as above, but it makes your

.feature file look nicer. Gherkin doesn’t care about that, only that

the number of columns match.

Speaking of Scenario Outlines, as seen in our previous entry, these are

very useful to specify many cause-effect relations:

When I do <action>

Then I get a <result>

Examples:

| <action> | <result> |

| Drink coffee | Be more alert |

| Take a cab | Get there faster |

| Open the window | Ventilate the room |

Detailed attack vectors

Let us put these to practice by documenting a vulnerability in detail

from our good old friend bWAPP,

which simply gives us a cryptic message:

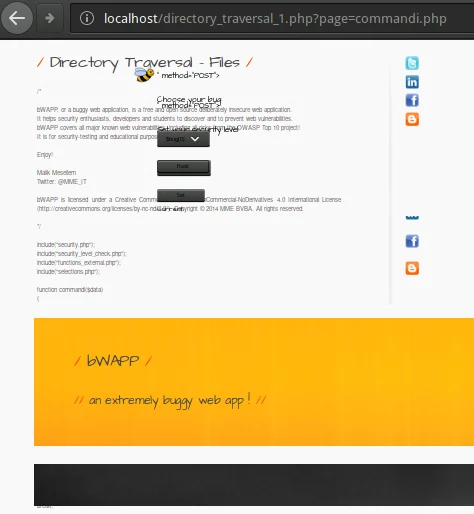

Figure 1. A mysterious message

No matter how dumb it might seem, this is the first thing we need to

document: how the page, app or whatever we’re testing works at the

moment we tested it. We might use a separate “Normal use case” scenario

as we did before.

Background

Or we can just plug that behavior right into the Background. This must

also include, in detail, everything needed to run the app. Our target

bWAPP is a PHP web server; Maybe you’re running it inside a

bee-box

virtual machine? Or did you set up the

LAMP

server yourself? On what operating system? All of this must be in the

background, in order to allow reproducibility.

I, for one, am running bWAPP inside a

Docker container made by

raesene, so let there be a

record of that in our attack feature:

Background:

Given I am running Manjaro GNU/Linux kernel 4.9.86

And I am running bWAPP 2.2 in Docker container raesene/bwapp:

"""

ubuntu 14.04 LTS, kernel=host(4.9), MySQL 5.5, Apache 2.4.7, PHP 5.5

"""

Given a PHP site showing a message:

"""

URL: bwapp/directory_traversal1.php?page=message.txt

Message: Try to climb higher Spidy...

Evidence: default-file.png

"""

All programs and versions are explicitly listed, plus the URL and

field where the vulnerability was found. Note how we can refere to

external evidence files, too.

Dynamic detection and exploitation

Now, the cryptic message in the page might be trying to tell us

something. Where can we climb? As it turns out, anywhere. The next hint

is in the URL. The page takes a GET parameter page=message.txt. So

the file message.txt is a simple text file that contains the words

above, and what the page does is display it. What if we change it to

another text file? Let’s try /commandi.php.

Figure 2. Abusing the website

Notice two things here: first, the PHP code and text commentaries are

shown. Hence we could theoretically access the PHP source of any page

in this server. Second, the HTML part is actually rendered in the

browser, which could lead to a XSS or

CSRF

attack.

But wait. The server is not just `floating'' in space: it lives inside a `GNU/Linux machine. And ‘everything’ in such an

OS is a file, many of which are plain-text files. One of them is of

particular importance:

/etc/passwd,

which stores information about users. Let us try to display it in this

page, setting page=/etc/passwd:

Figure 3. Listing users in the bWAPP servers

We can document that using Gherkin data tables, in a scenario of its

own, due to the importance of the finding:

Documenting a particular exploitation.

Scenario: Users record extraction

When I change the page=message.txt parameter to page=/etc/passwd

Then we retrieve the following user records:

# Records extracted

| username | pw? | UID | GID | info | home | shell |

| root | x | 0 | 0 | root | /root | /bin/bash |

| daemon | x | 1 | 1 | daemon | /usr/sbin | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| bin | x | 2 | 2 | bin | /bin | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| sys | x | 3 | 3 | sys | /dev | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| sync | x | 4 | 65534 | sync | /bin | /bin/sync |

| games | x | 5 | 60 | games | /usr/games | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| man | x | 6 | 12 | man | /var/cache/man | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| lp | x | 7 | 7 | lp | /var/spool/lpd | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| mail | x | 8 | 8 | mail | /var/mail | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| news | x | 9 | 9 | news | /var/spool/news | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| uucp | x | 10 | 10 | uucp | /var/spool/uucp | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| proxy | x | 13 | 13 | proxy | /bin | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| www-data | x | 33 | 33 | www-data | /var/www | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| backup | x | 34 | 34 | backup | /var/backups | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| list | x | 38 | 38 | Mailing List Manager | /var/list | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| irc | x | 39 | 39 | ircd | /var/run/ircd | /usr/sbin/nologin |

| gnats | x | 41 | 41 | Gnats Bug-Reporting System (admin) | /var/lib/gnats | /usr/sbin/nologin |

Now we know how many users there are on the server, and which of them

have passwords set. Those are stored in

/etc/shadow

in the form of hashes, which can be cracked if the passwords are

weak. However, the shadow file, unlike

the passwd file, is protected:

Figure 4. A failure

‘Drat!’ Well, we’ll find a way around it, sooner or later. Now that we

got the hang of it we can try other files. Since we always do the same:

change page=message.txt to page=desired-file.txt we can use a

Scenario Outline for that, using one column for what we give as input,

and the other for the result:

Documenting many cases in one Outline.

Scenario Outline: Dynamic detection and exploitation

Given the message and the page=message.txt GET parameter in the URL

When I change the GET parameter page=message.txt to another page=<path>

Then I see the file <printed> in the page, if it is a text file:

Examples:

| <path> | <printed> | <evidence> |

| /etc/passwd | User accounts info | passwd.png |

| /etc/group | User groups info | |

| /etc/shadow | Couldn't open | protected.png |

| /etc/hosts | Hosts file | |

| commandi.php | PHP source code and rendered HTML | source.png |

| passwords/heroes.xml | Heroes' passwords and secrets | |

| admin/settings.php | No output, but file exists | |

It is only natural to make several tries, some of which fail, some of

which succeed. All of them should be reported in the most scientific

spirit.

Static detection and possible fixes

Let us see why passwd could be read and shadow couldn’t. From

‘inside’ the server let us say

ls -l /etc/{passwd,shadow}

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1012 Feb 15 2016 /etc/passwd

-rw-r----- 1 root shadow 559 Feb 15 2016 /etc/shadow

Notice that passwd has three r’s: one for the owner (the user `root), one for the the owner’s group

(again, just root) and the final one is for everyone else. However

shadow doesn’t have that last r, so it can only be read by root.

While we’re at static detection of problems, let us see what is wrong

with that page so we can try to fix it. The source code for the page

simply takes the GET parameter page, and displays it.

Adapted from bWAPP code. Some lines and brackets omitted for

clarity.

$file = $_GET["page"];

show_file($file);

function show_file($file)

if(is_file($file))

$fp = fopen($file, "r") or die("Couldn't open $file.");

while(!feof($fp))

$line = fgets($fp,1024);

echo($line);

echo "<br />";

We can include this exact snippet, numbers and all, between

docstrings, while discussing code exploration in our feature file.

Now the main problem with this is that we can pass, as seen before, any

file as a GET parameter and it will be shown, i.e., that input should

have been validated and cleaned before show_file.

To fix that, a good first step would be to clean strings like .., ./

and ../, which is what you would generally use to “climb higher

Spidy”:

if(strpos($data, "../") !== false || strpos($data, "..\\") !== false ||

strpos($data, "/..") !== false || strpos($data, "\..") !== false ||

strpos($data, ".") !== false)

$directory_traversal_error = "Directory Traversal detected!";

This would block attackers who do not know the file system hierarchy in

the server, but still allows us to give absolute paths as the parameter.

An even better defense would be that the user should not be allowed to

display files outside the current folder:

// Gives the current directory path

$real_base_path = realpath("");

// Gives the absolute path equal to user input

$real_user_path = realpath($user_path);

if(strpos($real_user_path, $real_base_path) === false)

$directory_traversal_error = ""Directory Traversal detected!";

But this still allows us to display the file with the heroes’ passwords.

In fact, it would be better just not to allow users to display files at

their will.

More details

So far, we’ve documented in Gherkin:

-

the background where we’re running the vulnerable app,

-

the dynamic detection and exploitation phase, with several examples

and evidences, -

the important records we were able to extract from the app,

-

the static detection part, with specific bad code snippets, issues

and suggestions.

To finish a proper .feature file, we’re missing, well, the feature

itself, which is the vulnerability, or rather, the finding and

exploitation thereof.

Remember that we can document features and scenarios using

‘descriptions’. After the keywords Feature, Scenario, Scenario Outline or Example we can write anything we like, as long as no line

starts with a keyword (including comments – you can’t mix descriptions

with comments, I learned that the hard way).

It is usual to describe features with the format As <type of user> I

want to <do something> In order to <get some result>. We can take

advantage of such a structure to document the ‘Scenario’ and ‘Actor’ of

the vulnerability, the ‘Threat’ and what records can be ‘compromised’.

We can also use that space to document anything else we consider to be

globally important:

Feature: Vulnerability FIN.S.0075 Local file inclusion

From the bWAPP application

From the A7 - Missing functional level access controls category

In URL bwapp/directory_traversal_1.php

As any user from Internet with access to bWAPP

I want to be able to see local files I'm not supposed to

In order to gain access to system objects with sensitive content

Due to missing functional level access controls

Recommendation: restrict access to sensitive files (REQ.0176)

For anything else, use comments. I will include details such as the

vulnerability code, CWE,

CVE if present, computed metrics such as

CVSS scores, etc in comments

(#) at the beginning of the file. See the full feature

below.

And that is how we propose using this language to document attacks. You

may ask: why Gherkin and not just plain text? Because it is

line-oriented

and has a light structure, we can define a template like the one

discussed here, and we can enforce following of the format using the

readily available

parsers,

linters and

compilers for the language. We

still need to work further on the template definition, so stay tuned.

Appendix: full feature

local-file-inclusion.feature here

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Fluid Attacks RSS Feed authored by Rafael Ballestas. Read the original post at: https://fluidattacks.com/blog/gherkin-steroids/