This was H1 2022: Part 2 – Cyber War

On February 24, 2022, news broke that Russia had initiated its special military operation against Ukraine. That date, which marked the start of the war, will be engraved in our memories for a long time. Preceding the army movements, cyber operations attributed to the state actors of the Russian nation were already, for some time, waging against Ukraine. The cyber campaigns were the preludes that would have enabled Russia to achieve its ultimate goal swiftly; however, it was not the case. Ukraine, in war as in cyber, has had a long history of Russian assaults, and the people had become resilient against these attacks. For long before the war, Ukraine was anecdotally referred as “the testing grounds for Russian offensive cyber weapons.” For Ukrainians, denial-of-services attacks and defacements of government websites, fake SMS messages aiming to create chaos, was just another Monday morning. Due to Ukraine’s resilience and years of experience fighting and recovering from Russian cyber assaults, the attacks were a failure as they could not expedite or reinforce the progress of the Russian troops inside Ukraine.

What followed was a multitude of (cyber) battlefields, a cyber war, fought on many different levels, and not limited to the nations at war. New cyber legions were created, some rooted in government initiatives, others grown out of moral patriotism. Cybercrime groups and security organizations were reinventing themselves, repurposing their weapons and systems of defense, recalibrating their aims and creating a new offensive cyber force in an attempt to disrupt governments, create chaos, and dominate the news and influence public opinion.

Unfortunately, the battlefields were not always cleanly separated and actors distinguishable. Patriotic hacktivist operations provided great proxies for nations at war. Operations were not as clear-cut, and attribution became nearly impossible and not without implications as they could lead to retaliatory measures leading to a broader conflict. There are still many uncertainties in which legions and groups are independently working on achieving a common goal, and which ones are taking orders from a government body while merely becoming marionettes in a tactical game of thrones.

This blog is the second post in a three-part series to take a thematic look at cyber activities from the first half of 2022. It reviews the cyber events leading up to and occurring as a consequence of Russian’s invasion of Ukraine — a story of modern-day cyber warfare.

Prelude of an Invasion

As tensions mounted in Eastern Europe, on the night of January 13, 2022, hackers breached and defaced 70 Ukrainian government websites, posting provocative messages on the main page. CVE-2021-32648, a vulnerability in the OctoberCMS content management system, is believed to be the root cause behind the breaches.

On the same day, Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC) observed a destructive malware operation targeting multiple organizations in Ukraine. Microsoft identified intrusions originating from Ukraine that appeared to be a potential wiper activity. During their investigation, they found a new malware used in intrusion attacks against multiple victim organizations in Ukraine. The two-stage malware, dubbed WhisperGate, overwrites the Master Boot Record (MBR) on victim systems with a ransom note and subsequently downloads and executes a file corrupter destroying documents on the infected system. Initial access had apparently taken place through stolen credentials. Microsoft attributed the use of this custom malware to a threat actor that they refer to as DEV-0586. Mostly government, non-profit and IT organizations inside Ukraine were the targets of this operation.

On January 24, a hacktivist group known as the Cyber Partisans claimed credit for disrupting the network and databases of the national rail system in Belarus. The group posted on Twitter that they encrypted some of the Belarusian Railways’ servers, databases and workstations, with the objective to disrupt operations, but not affect automation and security systems out of safety concerns. In return for the encryption keys, the group demanded the release of political prisoners and ending the use of the transportation infrastructure to support Russian troop movements inside Belarus.

On January 24, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) warned about potential Russian cyberattacks, if Moscow would perceive the response to a possible Russian invasion by U.S. or NATO as threatening to Russia’s long-term national security. The memo, which DHS distributed to critical infrastructure operators and state and local governments, said “Russia maintains a range of offensive cyber tools that it could employ against U.S. networks —from low-level denials-of-service to destructive attacks targeting critical infrastructure.” Despite U.S. tensions with Russia over Ukraine, DHS analysts assessed that Moscow’s threshold for conducting disruptive or destructive cyberattacks on the U.S. homeland “probably remains very high.” The memo concluded as “[W]e have not observed Moscow directly employ these types of cyber attacks against U.S. critical infrastructure — notwithstanding cyber espionage and potential prepositioning operations in the past.”

On February 15, as Russian troops were amassing at the Ukrainian borders, Ukraine’s defense ministry, the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and two banks, Privatbank and Oschadbank, were taken offline by DDoS attacks. The Ukrainian cyber police also noticed fraudulent SMS messages reporting ATM failures sent to customers of a state-owned bank, coinciding with the DDoS attacks. Ukraine’s Security Service website was also not loading at the time. The Ukraine cyberpolice determined that the events were an information attack to distract and cause chaos. These network outages occurred as Russia staged over 130,000 troops outside of Ukraine.

On the morning of February 17, the situation between Russia and Ukraine began to escalate as reports started to surface about government websites in Russia experiencing intermittent outages and a network outage impacting Vodafone in Luhansk, Ukraine. It was later determined that the outage in Luhansk was the result of sabotage and not a DDoS attack. Later that day, both the United Kingdom and the United States attributed the DDoS attacks seen on Tuesday, February 15, to the Russian Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU).

On February 21, exactly one day after the closing ceremonies at the Beijing Winter Olympics, Putin recognized Ukraine territories as independent, setting the stage for further conflict.

The following days would see a renewed round of DDoS attacks targeting the Ukrainian government, as well as the U.K. and the U.S. publishing a joint report about Sandworm’s new botnet, Cyclops Blink.

Shortly before the Russian invasion started on the morning of February 24, a new disk-wiping malware, dubbed HermeticWiper, was leveraged against organizations in Ukraine, and impacted hundreds of systems in their networks. The attack came just hours after a series of DDoS onslaughts knocked offline several important websites in the country. Once activated, the wiper would damage the Master Boot Record (MBR) of the infected computer, rendering it inoperable. The attackers had apparently exploited a known vulnerability in Microsoft SQL Server (CVE-2021-1636) to compromise at least one of the targeted organizations. The wiper did not have any additional functionality beyond its destructive capabilities.

Just an hour before Russian troops invaded Ukraine, Russian government hackers targeted American satellite company Viasat’s KA-SAT network that provides internet service to European customers. The attack resulted in an immediate and significant loss of communication in the initial days of the war for the Ukrainian military, which relied on Viasat services for command and control of their armed forces. The disruption of Viasat’s KA-SAT satellite is Russia’s most significant cyber success to date. The attack created significant damage that spread beyond Ukraine, but ultimately did not provide a military advantage to Russia.

[You may also like: Cyber Attacks and Threats Admist the Russian Invasion of Ukraine]

On February 24, Russia invaded Ukraine. Along with the physical invasion, the world was exposed to modern hybrid warfare. As the troops entered Ukraine, regional DDoS attacks followed with an objective of causing disruption and panic across the country. In addition to Ukraine being targeted, the Russian government and banking websites also began to experience several outages, which resulted in the Russian government deploying new digital defenses.

Proxies of a Cyber War

Following the DDoS attacks on February 15 and 16, the White House and the UK Government assessed that Russia was responsible and attributed the Ukraine DDoS incidents to Russia’s GRU. Stating that “Technical information analysis shows the Russian Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU) was almost certainly involved in disruptive DDoS cyber attacks” and that “the decision to publicly attribute this incident underlines the fact that the UK and its allies will not tolerate malicious cyber activity.”

The infosec community also observed the DDoS attacks on February 15 and 16. 360 Netlab reported that a Mirai botnet with its command and control (C2) server located in the Netherlands was involved in the attacks. Bad Packets independently reported the same C2 server carrying payloads belonging to the Katana botnet, a Mirai variant operated by Vegasec. The server, located in Wormer NL, was leased by a Dutch company and owned by Ecatel, an offshore bare metal server provider. Ecatel was contacted by the Dutch authorities and subsequently took the server offline.

Following the invasion of Ukraine and the escalation of the hybrid warfare, DDoS attacks leveraging botnets and targeting both sides, primarily government and financial institutions, were observed (Kentik1, Kentik2, 360Netlab).

On March 2, Zscaler disclosed evidence about DanaBot being leveraged in the Russo-Ukrainian war. Danabot, first discovered in 2018, is a malware-as-a-service platform where threat actors, known as affiliates, are identified by affiliate IDs. ZScaler uncovered that Danabot affiliate ID 5 used their access to the botnet to launch HTTP DDoS attacks against the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense’s webmail server. The DDoS attack was launched by leveraging Danabot to deliver a second-stage DDoS payload on the enslaved machine. Zscaler mentioned it is unclear whether this is an act of individual hacktivism, state-sponsored, or possibly a false flag operation.

Ransomware Groups Divided by Conflict

On February 25, Conti Team officially announced their full support of the Russian government on their dark website: “If anybody will decide to organize a cyberattack or any war activities on against Russia, we are going to use our all possible resources to strike back at the critical infrastructures of an enemy.” The ransomware gang changed their message one hour later, stating that they “do not ally with any government and condemn the ongoing war,” but that they will respond to Western cyber aggression on Russian critical infrastructure. Conti is one of the most active ransomware groups in the industrial sector and is considered highly sophisticated. Conti was responsible for breaching 63 companies operating industrial control systems (ISC) in 2021. Conti is also known for being the first group to weaponize the Log4Shell vulnerability.

Days after Conti announced their support for Russia, an insider who is believed to be Ukrainian leaked internal communications between members of the group, messages that go back to January 2021. The data was shared on vx-underground. The hacking collective that leaked the Conti information is now referred to as “ContiLeaks.”

On February 28, AlphV (aka BlackCat, Noberus) ransomware condemned Conti’s support of the Russian government on their underground ‘customer support’ site, stating that “[They] are extremely saddened by what is happening. In [their] business, there are no nationalities, fictional borders, or any other reason why people can kill people.”

On February 26, CoomingProject shared on their Telegram channel they “will help the Russian government if cyber attacks are conducted against Russia.”

Also in February, the administrator of the Raidforums marketplace announced that “any user found to be connecting from Russia will be banned! This is not a joke, we do not support the Kremlin.” Another member of the Raidforums community reacted by posting a database containing emails and hashed passwords for the FSB.ru domain.

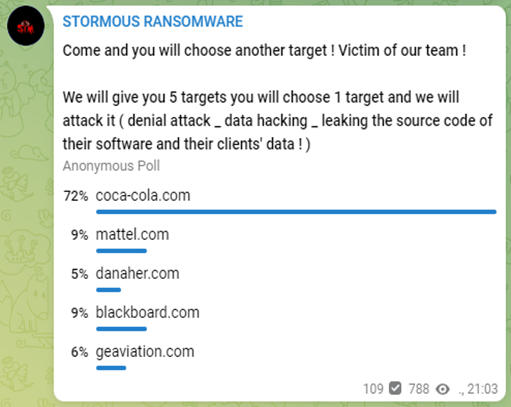

On March 1, the Stormous ransomware group officially announced its support for the Russian government and claimed to have attacked the Ukraine Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a Ukrainian airline. On April 24, the Stormous gang posted to its website that it had attacked Coca-Cola, after taking a poll on Telegram asking followers to choose their next victim. Stormous claimed that they took 161GB of data, including financial information, credentials, and other sensitive information from Coca-Cola’s servers, and were trying to sell the stolen data for little over 1.6 Bitcoin ($62,000). While Coca-Cola has not officially confirmed that the data was stolen, it told BleepingComputer that it was investigating the alleged attack. On March 7, the group claimed to have obtained 200GB of data belonging to Epic Games, including information of 33 million users.

Cyber Legions

On February 26, Mykhailo Fedorov, Vice Prime Minister of Ukraine and Minister of Digital Transformation, announced on Twitter, the creation of a cyber volunteer army that would act on operational tasks submitted through a Telegram channel—encouraging civilian IT volunteers around the globe, emotionally attached to the cause of Ukraine, to use any vectors of cyber and DDoS attacks on Russian state, financial and business corporations.

“Born out of necessity, the IT Army evolved into a hybrid construct that is neither civilian nor military, neither public nor private, neither local nor international, and neither lawful nor unlawful.” — Stefan Soesanta, Center for Security Studies, ETH Zurich – The IT Army of Ukraine: Structure, Tasking, and Ecosystem

On March 1, Cyber Unit Technologies, a Kyiv-based cybersecurity firm, announced a bounty program to reward hackers for taking down Russian websites and pledged an initial $100,000.

On March 22, the deputy head of the Ministry of Industry and Trade proposed to think about creating cyber troops in Russia and a state defense order in this area.

On March 24, the website of the National Bank of Poland (NBP.pl) was knocked offline by a DDoS attack. The pro-Russian hacktivist group Killnet claimed the attack and called it “a warning” directed at the Polish government to avoid more involvement in the Russo-Ukrainian war.

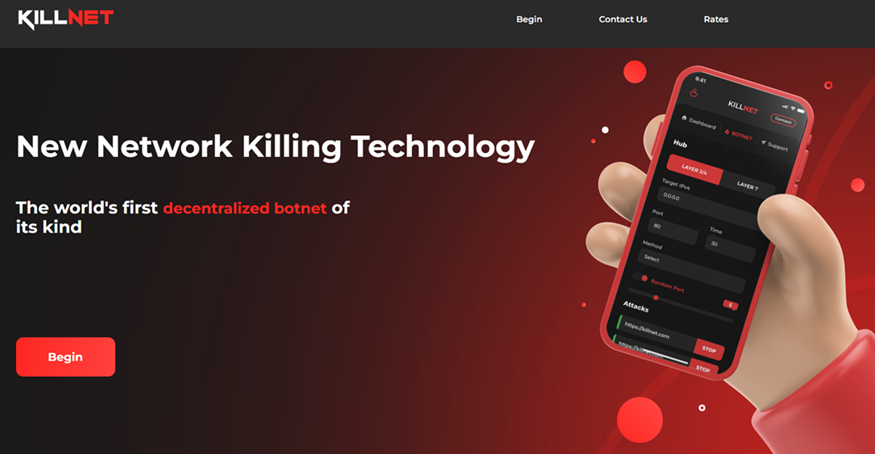

Killnet is a pro-Russian hacktivist group that became active near the end of February. In three months, they gathered a following of over 63,000 subscribers on their Telegram channel and more than 34,000 subscribers on their media page ‘Cyberwar.’ In a video addressing the people of Russia, Killnet declared cyberwar on those that support the U.S. intervention in Ukraine. Killnet claims its members are ordinary people and denied any association with the Russian government.

Before the invasion, the group Killnet was selling access to a DDoS botnet which they claimed consisted of 700,000 bots and had an aggregate 3.6Tbps attack capacity. They advertised it as the “New Network Killing Technology” and “The world’s first decentralized botnet of its kind.”

On March 15, in an act of protest against the invasion of Ukraine, the maintainer of a popular Node.js module named “node-ipc,” deliberately sabotaged his module. The module, providing local and remote inter-process communication (IPC), is leveraged by many neural network and machine-learning tools. The developer altered his code to deliberately corrupt files on systems running applications that depend on the “node-ipc” module, but only if those systems were geolocated in either Russia or Belarus, in what can only be described as a software supply chain attack impacting the “npm” ecosystem.

On March 29, the Connecticut Airport Authority (CAA) was notified about cyber attacks on the website of Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut. The DDoS attacks were mitigated while the website remained mostly live. The incident was isolated to just the website and airport operations were not impacted. Killnet took credit for the attacks and said that these were the start of a campaign against the United States, in retaliation for the supply of weapons to Ukraine.

On April 8, during an address to Parliament, by Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky, the websites of the government of Finland were targeted in a cyberattack. The websites of the Finish foreign affairs (um[.]fi and finlandabroad[.]fi) and defense ministry (defmin[.]fi) were disrupted briefly by the DDoS attack. In the days leading up to the attack, several reports suggested that Finland was considering to seek NATO membership, a move vehemently opposed by the Kremlin.

On April 12, hours after Currency.com, a global cryptocurrency exchange, announced that it was halting operations for Russian residents, it became the target of a (failed) DDoS attack. Viktor Prokopenya, the founder of Currency.com, said his firm faced a massive backlash after it decided to pull the plug on Russians, with call-center staff immediately facing abuse and death threats.

Between April 20 and 21, the pro-Russian threat group Killnet, targeted several Czech entities with DDoS attacks. The Czech National Cyber and Information Security Agency (NCISA/NÚKIB) reported severe DDoS attacks on Czech critical services. The Czech railways reported outages in the Můj vlak (My Train) mobile app. Buying tickets and finding connections became problematic. The Karlovy Vary Airport website was targeted but remained accessible from within the Czech Republic. The Pardubice Airport was less fortunate and reported failures of the entire web system and website. The airport operations, however, were not affected. The public administration portal and later the website of NÚKIB (NCISA) itself were attacked. The NCISA reported on Twitter, “Due to the DDoS attack, it may happen that the website will not be accessible from abroad.” The website, however, did remain accessible from within Czechia.

On April 22, Ukraine’s national postal service Ukrposhta was hit by a DDoS attack targeting its online store and systems. The attacks started soon after the sales of a postage stamp depicting a Ukrainian soldier making a rude gesture to a Russian warship went online. The stamp was released following the sinking of the flagship of Russia’s Black See Fleet and generated a lot of attention and demand, leading to long queues to buy the stamp after it went on sale at the postal headquarters in Kyiv.

On April 29, the pro-Russian hacktivist group Killnet claimed credit for DDoS attacks on gov[.]ro (Romanian government’s domain), mapn[.]ro (Romanian Ministry of Defense), politiadefrontiera[.]ro (Romanian Border Police), cfrcalatori[.]ro (Romanian National Railway Transport company) and optbank[.]ro (a commercial bank operating in Romania). Romania has been supporting Ukraine throughout the war, providing humanitarian support to refugees fleeing the conflict. Earlier in the week of the attacks, Romanian parliamentary speaker Marcel Ciolacu visited Kyiv for talks with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky about how the countries can co-operate on security in the future.

In the beginning of May, the IT Army of Ukraine disrupted the supply chain of Russian alcohol producers by targeting the Russian federal state-owned automatic system for tracking the production and distribution of alcoholic beverages with DDoS attacks. IT Army was able to take down the EGAIS system, due to which factories could not accept tanks with alcohol, and consequently, customers, stores and distributors could not receive shipments. The attacks on EGAIS began on May 2. Ladoga faced similar attacks on May 3, while Fort was disrupted on May 4. Beluga Group, the Russian manufacturer of strong alcoholic beverages, did not notice any problems.

On May 9, Victory Day in Ukraine, Russian hackers launched massive DDoS attacks on the websites of leading Ukrainian telecom operators. Despite the websites’ unavailability, the targeted operators’ networks were not disrupted. The Ukraine government stated that “the cyberattack was likely intended to be used for waging yet another PSYOP against Ukrainian people. Russian criminals are trying to deny Ukrainians access to the Internet and true information, to spread panic.”

On May 11, the websites of the Italian senate, the military and the National Health Institute faced disruptions by DDoS attacks. The attack also affected the Automobile Club d’Italia and several other Italian institutions. Killnet took credit for the incidents. Some of the sites were down for several hours.

On May 15, the Italian police announced that they thwarted attacks during the May 10 semi-final and Saturday final of the Eurovision Song Contest in Turin, Italy. Ukraine’s Kalush Orchestra won the contest with their entry “Stefania,” followed by a wave of public support to claim an emotional victory welcomed by the country’s president Volodymyr Zelensky. During voting and the performances, the police cyber security department said that it had blocked several cyber attacks on the Eurovision network infrastructure by the “Killnet” hacker group and its affiliate “Legion.”

On May 17, the German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution published a safety advice note warning about DDoS attacks against various German websites from the private sector and research institutions by a cybercrime group Killnet.

On May 10, speaking at the CyberUK conference, the cybersecurity director of the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), Rob Joyce, said that the re-emergence of online vigilantes, or hacktivists, during the war in Ukraine could prove “problematic” for wider security efforts. Head of the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) Abby Bradshaw added that these hackers can introduce “extreme unpredictability” for intelligence services and that there is potential for “spillover and wrongful attribution, retribution and escalation” of cyber conflict.

“The re-emergence of online vigilantes, or hacktivists, during the war in Ukraine could prove problematic for wider security efforts.” — NSA Cybersecurity Director, Rob Joyce

“These hackers can introduce extreme unpredictability for intelligence services and there is potential for spillover and wrongful attribution, retribution and escalation of cyber conflict.” — Head of the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), Abby Bradshaw

On June 15, the IT Army of Ukraine posted a task for its followers to “visit” the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) that same day. The DDoS attack on the resources of the SPIEF, also known as the “Russian Davos,” shut down the admissions and accreditation systems and consequently delayed the speech from Russian President Vladimir Putin for more than an hour. Reuters reported that Putin gave his speech 100 minutes after the scheduled start time. According to the forum’s secretary of the organizing committee, the attacks amounted to 140 gigabits per second.

In June, the IT Army of Ukraine posted a job advertisement for hiring DDoS specialists on their Telegram and website. The requirements include knowledge of network architectures, understanding the intricacies of high-level protocols (applied to HTTP and transports like TLS), experience with load balancers, and ideally, experience with DDoS countermeasures. The offer was to “Work entirely on a volunteer basis and will require a lot of free time. At the moment, we are assembling a team for a permanent basis that can and will do this systematically. Therefore, if you understand this and have a lot of free time – leave a request.”

On June 27, Lithuania’s Secure Data Transfer Network, a communications network for government officials that was built to withstand war and other crisis, was disrupted by DDoS attacks. The morning of the attacks, Killnet released a video message on the group’s Telegram account threatening to attack Lithuania continuously until they allow the transit of goods to Kaliningrad. Days earlier, Lithuania, a member of NATO, announced a ban on the transit of goods subjected to EU sanctions through its territory to the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad. The banned goods include coal, metals, construction materials and advanced technology, making up 50% of Kaliningrad’s imports. The National Cyber Security Centre (NKSC) under the Ministry of National Defense warned of intense and ongoing DDoS attacks against the Secure National Data Transfer Network, governmental institutions, and private companies in Lithuania, which could cause disruptions and might continue for several days. By July 9, Killnet started targeting the Lithuanian energy supplier Ignitis Group. Ignitis, which serves 1.7 million customers in Lithuania, described the attack as “the biggest cyberattack [it has faced] in a decade.” It said, “Strong DDoS attacks [are] causing disruptions to the operation of group websites and the availability of electronic services.”

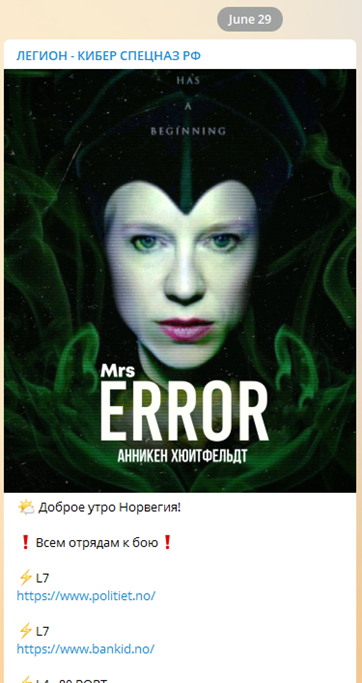

On June 29, the Norwegian authorities said that a cyberattack temporarily disrupted public and private websites in the past 24 hours. Norway’s National Security Authority (NSM) accused pro-Russian hackers of launching several DDoS attacks at a number of critical organizations in the country. The NSM’s director, Sofie Nystrøm, released a statement saying that several large Norwegian organizations were taken offline by the attacks in the last 24 hours. “Good morning Norway! – All squads at battle!” was posted in the Telegram channel of pro-Russian hacker group Legion, a member of the Killnet cluster, on the morning of the attacks. The announcement was framed by a manipulated photo of Norwegian Foreign Minister Anniken Huitfeldt, by the hackers named “Mrs. Error.” The attacks are believed to be related to Moscow accusing Oslo of blocking food supplies from reaching Russian miners in the Arctic region via mainland Norway. On July 6, Russian and Norwegian officials said they settled the dispute over coal mining shipments to the archipelago of Svalbard.

Anonymous 2022

The “bring your own chapter” culture which Anonymous turned into, leads to a fair amount of fragmentation and uncoordinated attack campaigns. The only thing most chapters have in common, for now, is a Russian enemy. The most prominent activity of many chapters is limited to offensive messages, claims of hacks in the absence of evidence and the spread of incorrect information. Anonymous is missing the community and drive which DragonForce Malaysia was able to bring back in larger hacktivist groups that can make an impact. DragonForce Malaysia is growing more professional each day. One member of DragonForce Malaysia told us that the day before an actual campaign attack, all members synchronize and join for a test, ensuring that on D-day, they bring their A-game. Anonymous used to have the core leadership, but as the team dissolved a few years back, all that is left is an idea, a name and a mask that fits anyone who believes apt to do so.

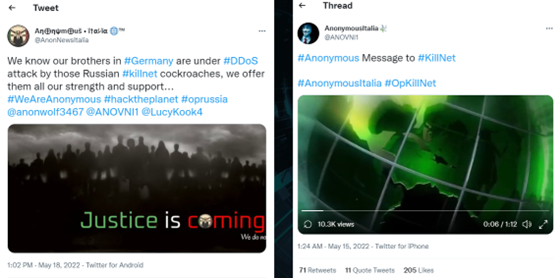

After the DDoS attacks targeting Italian government and private websites, and the attacks on the Eurovision Song contest in the first half of May, the Italian chapter of Anonymous declared war on Killnet. Several offensive messages were published on Twitter by several Anonymous accounts claiming allegiance to the Italian Anonymous branch.

Killnet soon countered these messages in a message posted on their Telegram, mockingly entitled “WE ARE KILLNET” and replying directly to the message “Justice is coming” from @AnonNewsItalia on Twitter.

In June, a now suspended account @PucksReturn tweeted, “Anonymous presents DDoS tools. Do not use irresponsibly.” It also tagged OpRussia and Ukraine while linking to a document on Lulzbin. Upon further inspection, the document covering the DDoS tools contained a portion of an advisory published by Radware, including the Radware footer for “Effective DDoS Protection Essentials” and “Effective Web Application Security Essentials.” Knowledge is free indeed, @PucksReturn.

On June 27, in response to the Killnet DDoS attacks on Lithuania, a Twitter account @OpFuckKillnet, which joined in May 2022 and launched #OpFuckKillnet with the threatening words of “Expect us,” tweeted a photograph of a group of people. The account claimed to be exposing the real identities of the members of Killnet to the larger Anonymous community. The message and picture were retweeted and reposted by several other Anonymous-associated accounts. Until, a few days later, a person with the Twitter account @miglen posted that the photo originated from a recent infosec meetup he and his friends attended in Sofia, Bulgaria and that the picture had been “leveraged” by someone to claim they conspire with Killnet.

DoomSec is an Anonymous affiliated hacktivist group that supports OpRussia and OpKremlin through their Twitter, Telegram and their website doomsec[.]org on the clear net. The group describes itself as “a group made of hacktivists who are doing what they believe is the best for the preservation of social equity and equality.”

Playbooks Rewritten

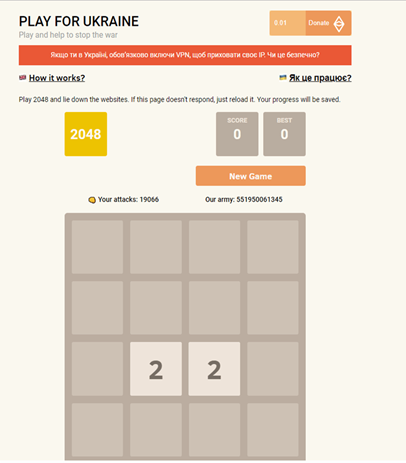

Gamification, webification and drive-by DDoS Attacks

The IT Army of Ukraine brought hacking to the masses, including teens, via gamification of denial-of-service attacks. This included the playforukraine[.]life website, an online game of 2048 created by Lviv programmers to help Ukraine fight Russian aggression. One player can send about 20,000 requests per hour of play to block sites that serve the Russian army. The exact list, however, was never disclosed for security reasons.

On March 18, @playforukraine1 tweeted about one of their accomplishments: knocking the website dominospizza[.]ru offline and addressing the Russian population with the statement, “Russians, if people in Mariupol cannot live a normal life and have food, then you have no right to do so.”

“Russians, if people in Mariupol cannot live a normal life and have food, then you have no right to do so.” — @Playforukraine1

Very similar, but not masquerading as a game, the stop-russian-disinformation.near[.]page starts flooding a list of Russian online targets curated by the website owners as soon as the page is loaded in the browser.

On March 28, MalwareHunterTeam discovered that hackers were compromising WordPress sites and injecting malicious code that abuses visitor’s browsers to perform denial-of-service attacks against Ukrainian websites. Any visitor of a breached WordPress site basically became a bot, performing application-level denial-of-service attacks that were targeting a list of websites curated by the authors of the malicious code.

On April 28, the Government’s Computer Emergency Response Team of Ukraine (CERT-UA), in close cooperation with the National Bank of Ukraine, discovered, upon investigating DDoS attacks, malicious JavaScript code, dubbed “BrownFlood,” in web pages and files of compromised WordPress websites. The script, encoded in base64 to avoid detection, executes in the compromised website visitor’s browser, leveraging the users’ resources to attack a hardcoded list of Ukrainian websites. One month earlier, the same JavaScript script, which was readily available on GitHub, had been involved in DDoS attacks against a smaller pool of pro-Ukrainian websites. It then came to light that a particular pro-Ukrainian site had also used that same JavaScript code to target Russian websites with DDoS attacks.

disBalancer LIBERATOR

On March 4, disBalancer launched a new application named Liberator, calling it “an entirely new level to fight Russian propaganda outlets.”

Before the invasion, the disBalancer project was aiming to be a global, fully decentralized, peer-to-peer network providing load balancing services and resistance against DDoS attacks by “harnessing the same unused internet bandwidth and storage manipulated by malicious actors, by incentivizing those vast resources to fight against DDoS rather than for them [DDoS].” Anyone owning a computer or smartphone would run the disBalancer peer client in the background on their device, renting out their unused bandwidth and storage, and earn disBalancer tokens (aka DDOS tokens), a newly introduced crypto coin, as an incentive reward. Businesses looking to protect their websites would acquire DDOS tokens and request services from the network in a matter of clicks. Network nodes could be set up on any Linux, Windows, Android, iOS, or macOS device, and would automatically run in the background when users would choose to allow so. Users became part of local verification pools to handle demand closest to them, earning DDOS tokens as a reward from the shared pool for all the traffic received and sent. Users could then sell DDOS tokens back to the websites to cover network usage costs, or utilize them in other yield farming opportunities across the blockchain ecosystem, creating an economic cycle that would promote the growth of the disBalancer network.

By reverting their original plan to harness volunteered resources to fight DDoS rather than perform it, disBalancer created the first volunteered botnet. Anyone downloading and installing the Liberator application on their desktop or laptop was turning their system into a capable bot performing DDoS attacks against a list of Russian (for now) targets curated by the disBalancer team. People running the application in the background donated their compute and internet resources for pro-Ukraining assaults on their Russian enemies, fully managed by the disBalancer team.

[You may also like: Is DDoS a Crime?]

To further the cause, a famous influencer named Boxmining, discussing cryptocurrency trends and not giving financial investment advice on YouTube, with over 250,000 subscribers, posted a video calling his subs to “join the cyber warfare against Russia to stop that Russian propaganda machine.” Boxmining asked people to download and install the Liberator app. He told them how to bypass the security features of their system to install the packages and claimed that it was entirely benign and legitimate because he had a long talk with the creators of the application and was assured that it was legit, even though the end-point protections were notifying users and detecting the application as a malicious and dangerous.

On May 23, the disBalancer team published the first Liberator statistics, which covered three months from the start of the invasion on February 24 until May 23. In those three months, according to the Liberator statistics shared by disBalancer, 100,000 people downloaded the Liberator application, and the peak number of concurrently active bots performing DDoS attacks was 7,200. A total of 275 Russian services were attacked, and contrary to the claims of fighting Russian propaganda, more than a third of the attacks were targeting “vital resources used by common people in Russia,” while only one-fifth of the attacks were actually targeting propaganda related targets.

If installing a malicious application or running a program in the background that consumes all your resources to perform DDoS attacks sounds too sketchy, there is always the option to invest in DDOS tokens. Hold at least 1,000 DDOS tokens when the war ends, and you will become the “proud” owner of the “Veteran of the First Cyber War” NFT medal.

The IT Army of Ukraine automated DDoS bot

In March, the IT Army of Ukraine announced the availability of a bot that allowed them to orchestrate DDoS attacks against Russian targets, through a volunteer-based botnet controlled by a Telegram channel, much like an IRC botnet, but leveraging Telegram for command and control instead. Until then, the IT Army had gathered a fair following of people in and outside Ukraine. Telegram group members would perform DDoS attacks on a list of targets that were updated and posted daily on the channel. Members were still responsible for manually running the attacks, leveraging several tutorials published on the website of the IT Army of Ukraine.

The tutorials provided by the IT Army website included installation instructions and demonstrated the use of widely known and publicly available denial-of-service tools such as MHDDOS, Death By a 1000 Needles (DN1000N) and DSTRESS. The site also provided tutorials explaining how to leverage (abuse) free tiers on popular cloud computing platforms such as AWS, GCP, Azure and DigitalOcean.

However, one problem that the IT Army faced was that attacks were not synchronized and consequently did not hit as hard as they could because traffic was spread over time. To create more impactful attacks, the IT Army needed to synchronize them through orchestration, introducing the IT Army of Ukraine Automated DDoS Bot.

The IT Army’s automated bot consists of a Docker container that could run a customized version of MHDDOS. The automated bot tutorial explained how containers could be started through a single docker command line, and how the user needs to create a comma-separated file containing the IP addresses, the admin username and the cleartext password and then upload that file to the Telegram channel @gov_ddos_ru_bot. At that point, the Telegram command and control service would take over the container. Whenever the botnet administrator performed attacks, the owners of the bots would be informed of the ongoing attacks and the target through Telegram notifications.

Another customization of the MHDDOS tool leveraged by the automation bot included download locations of obfuscated lists containing 800+ free HTTP and SOCKS4/5 proxies that could be leveraged during the application-level DDoS attacks. The list was maintained by the IT Army core members, and according to a snapshot and verification through Shodan[.]io, a fair amount of the proxies are MikroTik routers with SOCKS service enabled and exposed to the internet (Meris anyone?).

Фронтон, a botnet for coordinated inauthentic behavior

In 2020, a group called “Digital Revolution” leaked documents and contracts from a subcontractor to the FSB, about a contracted IoT botnet known by codename Fronton (Фронтон) and built by a contractor named ‘0day Technologies.’ One of the aims of the botnet was to perform DDoS attacks to the level of being capable of turning off the internet in a small country.

Based on documents leaked a day later, Nisos could determine that DDoS was only one of the many capabilities of Fronton. Nisos determined, based on the leaked documents, that Fronton was a system developed for coordinated inauthentic behavior on a massive scale. The system included a web-based dashboard, known as SANA, enabling users to formulate and deploy trending social media events en masse. The system creates events called “newsbreaks,” utilizing the botnet as a geographically distributed transport.

SANA created social media persona accounts, including provisioning of an email and phone number. In addition, the system provided facilities for creating newsbreaks on a schedule or a reactive basis. One example, included in the data, involved comments around a squirrel statue in Almaty, Kazakhstan that may have affected the reporting on a BBC story. As of April 2022, 0day Technologies has changed its domain from 0day[.]ru to 0day[.]llc. An instance of the SANA system appeared at https://sana.0day[.]llc when Nisos wrote the report. Nisos assessed that this is possibly a testing or demo instance and not currently used by the FSB.

Is This a Cyber war?

Nations across the world are being vigilant, strengthening their defenses in preparation for a potential escalation into what could become a global conflict in cyber space. Others see an opportunity and leverage the chaos to accelerate and increase their offensive operations at a time the Russo-Ukrainian conflict is the priority and focal point for most western nations.

On April 20, the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) published an alert (AA22-110A) warning organizations that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could expose organizations both within and beyond the region to increased malicious cyber activity. This activity might occur as a response to the unprecedented economic sanctions imposed on Russia as well as the material support provided by the United States and its allies and partners. The alert mentioned the recent Russian state-sponsored operations, including the DDoS attacks at the beginning of the invasion, and warned about Russian-aligned cybercrime groups threatening U.S. critical infrastructure with ransomware and DDoS attacks.

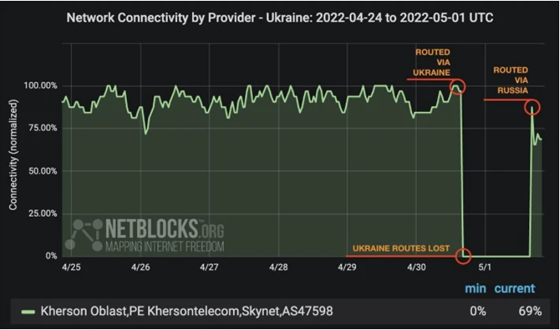

On May 1, network connectivity in Russia-occupied Kherson provided by local internet provider SkyNET switched to Russia’s Rostelecom. On April 30, mobile connections were shut down in the areas of Ukraine’s Kherson region. A representative of the Vodafone mobile operator told Ukrainian broadcaster Suspilne Kherson that “this is not an accident.”

On June 15, Yurii Shchyhol, Head of Ukraine’s State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection, published his preliminary conclusions drawn from the Russo-Ukrainian war in the Atlantic Council. Shchyhol wrote that the invasion was developing into the world’s first full-scale cyberwar, and it would take many years to digest the lessons of this conflict fully. Shchyhol continued that “the current war has confirmed that while Russian hackers often exist outside of official state structures, they are highly integrated into the country’s security apparatus and their work is closely coordinated with other military operations. Much as mercenary military forces, such as the Wagner Group, are used by the Kremlin to blur the lines between state and non-state actors, hackers form an unofficial but important branch of modern Russia’s offensive capabilities.” Adding that “just as the Russian army routinely disregards the rules of war, Russian hackers also appear to have no boundaries regarding legitimate targets for cyber-attacks.”

“The Russo-Ukrainian War is the world’s first full-scale cyberwar but it will not be the last. On the contrary, all future conflicts will have a strong cyber component. In order to survive, cyber security will be just as important as maintaining a strong conventional military.” — Head of Ukraine State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection, Yurii Shchyhol

In June, Stefan Soesanto, a Senior Researcher in the Cyberdefense Project with the Risk and Resilience Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich published a report detailing the tactics, techniques and procedures leveraged by the Ukrainian Intelligence Services and the IT Army of Ukraine and its complex interactions with non-state third parties. Stefan concluded that:

“Both Kyiv and the Ukrainian IT community at large have shown the world what digital diplomacy on steroids looks like. Their conduct has collapsed entire pillars of existing legal frameworks regarding norms and rules for state behavior in cyberspace and has taken apart the illusion of separating the defense of Ukraine from Ukrainian companies and citizen living abroad.” — Stefan Soesanto, Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich

On June 1, General Paul Nakasone, Commander of the U.S. Cyber Command and Director of the NSA, confirmed for the first time that the United States had engaged in offensive cyber operations against Russia in support of Ukraine during an interview with Sky News. General Nakasone also explained how “hunt forward” operations allowed the United States to search out foreign hackers and identify their tools before they were used against the U.S. The statement from General Nakasone caused a stir. Days after General Nakasone’s statement, Russia appeared to interpret Nakasone’s remarks as the U.S. shifting its policy. The Russian foreign ministry warned the U.S. not to provoke Russia with cyberattacks or it would take “firm and resolute” retaliatory measures with potentially catastrophic results. “[T]here will be no winners in a direct cyber clash of states,” the ministry said. But when asked during a White House press conference whether the offensive cyber operations contradicted the administration’s policy against direct involvement in the conflict, press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said they didn’t. Kim Zetter, a journalist covering cybersecurity and national security, author of “Countdown to Zero Day: Stuxnet and the Launch of the World’s First Digital Weapon,” wrote an excellent blog addressing and clarifying the wording used by Nakasone. During an interview, Zetter asked Gary Corn, former general counsel for U.S. Cyber Command from 2014 to 2019 and now director of the Tech, Law and Security program at American University: “What might the U.S. do that doesn’t risk being drawn into the conflict?” Corn answered: “If Russia tried to defeat Ukrainian morale or conduct information operations against Ukraine, the U.S. could use a cyber operation to undermine or thwart their ability to send messages in some way and this wouldn’t be a use of force, depending on the technique they used and the effect it had on Russian systems.”

“The United States engaged in offensive cyber operations against Russia in support of Ukraine.” – Commander of the U.S. Cyber Command and Director of the NSA, General Paul Nakasone

Kim Zetter explained there was a lot of confusion around General Nakasone’s comments because it was unclear what kinds of operations the term “offensive cyber operations,” also known as OCO in military parlance, included. Nakasone perhaps intentionally left his comments vague, and both the White House and U.S. Cyber Command declined to elaborate, simply referring reporters back to his oblique interview. The operations could include a combination of reconnaissance and attacks intended to have an effect on systems as defined by military doctrine. But this did not mean that the U.S. had been destroying Russian systems. There was a vast spectrum of activity that could qualify as a cyberattack, from operations that produced only very subtle effects to ones that physically destroyed equipment and potentially crossed a line into a use of force.

On July 1, DTEK Group, Ukraine’s biggest private energy conglomerate, said that the Russian Federation carried out a cyber attack on the group’s IT infrastructure. DTEK, which owned coals and thermal power plants in various parts of Ukraine, said that the goal of the attackers was to destabilize the generation and distribution of electricity in Ukraine. The cyber incident was reported at the same time when it was reported that a missile attack on the Kryvorizka Thermal Power Plant had taken place, attacking the company’s digital infrastructure.

A few days earlier, on June 29, XakNet Team claimed to have breached the Ukrainian private energy firm DTEK Group on their Telegram channel. XakNet Team’s chats mention that no harm was done to the operations, but they would get back to DTEK with terms for an exchange of the backdoors they exploited in the DTEK network. They also added that they were not out for money, which fitted the narrative of a hacktivist group.

XakNet is a pro-Russian hacktivist group created on March 1, 2022, after the invasion started. The collective called itself a “team of Russian patriots” and criticized Anonymous for hiding behind a mask. In their announcement they threatened, “For every hack/ddos in our country, similar incidents will occur in Ukraine.”

Earlier in the year, in January, a post from a user selling DTEK employee credentials was spotted on RaidForums, whose domain would be seized by the FBI later in the year. Underground forums chatter revealed that DTEK was also a target of Raccoon Stealer. Raccoon Stealer was an information-stealing trojan offered as malware-as-a-service for $75 per week or $200 per month. Threat actors who subscribed to the operation got access to an admin panel that let them customize the malware, retrieve stolen data, and create new malware binaries. The cybercrime group behind Raccoon Stealer suspended their operation in March, after they lost one of their developers to the war, but made a return in June.

Russia and China, Still Friends Without Limits?

According to a recently published report by Cybersixgill intelligence analysts, the Sino-Russian alliance appears to remain resilient amid the increasingly volatile geopolitical tensions. Despite Chinese President Xi Jinping’s and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s joint proclamation of their “friendship without limits” in February 2022, Putin’s subsequent invasion of Ukraine certainly dampened China’s enthusiasm. The uncertainty surrounding the war’s outcome is forcing Xi Jinping into a tenuous balancing act that preserves the partnership with Putin while still prioritizing China’s global interests. Regardless of the war’s outcome, however, the balance of power in this bilateral alliance had already tilted in China’s favor, with Moscow more reliant on Beijing than ever — geopolitically and economically. These dynamics between leaders were somewhat mirrored on the underground. While Chinese threat actors took interest in the conflict from a distance, and happily participated, collaborated, and learnt from the expertise of their Russian cybercriminal counterparts, the enthusiasm seemed to be similarly one-sided. Russian cybercriminals continued to make overtures to their Chinese peers, discussing even within their own Russian-language forums ways to reach out and deepen this cross-border partnership. Like their President, however, Chinese threat actors remain guarded, collaborating on the basis of pragmatic, strategic self-interest. Cybersixgill concluded that given Russian-speaking cybercriminals’ sophistication and their constantly evolving modus operandi, the transfer of this knowledge to Chinese threat actors was especially concerning.

“Should this Russian and Chinese alliance continue, a devastating new non-state cyber superpower may emerge, unchecked by diplomatic concerns or fears of destabilizing the international order.” — Cybersixgill

Don’t miss the other blogs in our three-part series, highlighting other notable cyber activities from the first half of 2022. Our final post covers events, attacks, and heists beyond the Russian and Urkraine cyber war. Our first post takes a look at the increased efforts and successes of law enforcement and the global security community in their fight against cybercrime.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Radware Blog authored by Pascal Geenens. Read the original post at: https://blog.radware.com/security/2022/08/this-was-h1-2022-part-2-cyber-war/