When the Experts Disagree in Risk Analysis

Image credit: “Every family has a black sheep somewhere!” by foxypar4 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

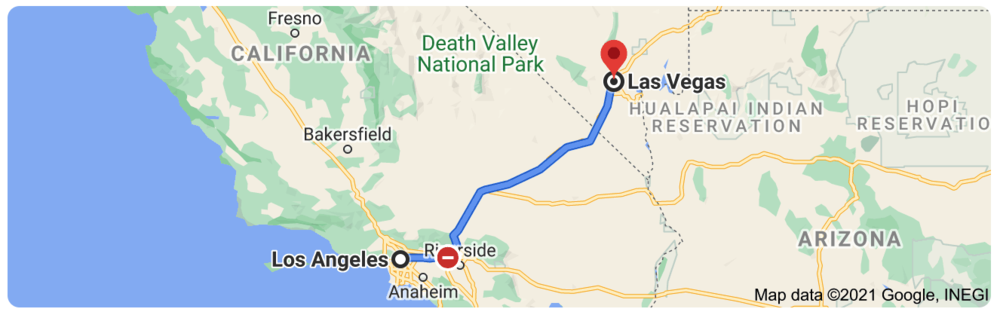

Imagine this scenario: You want to get away for a long weekend and have decided to drive from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. Even though you live in LA, you’ve never completed this rite of passage, so you’re not sure how long it will take given traffic conditions. Luckily for you, 5 of your friends regularly make the trek. Anyone would assume that your friends are experts and would be the people to ask. You also have access to Google Maps, which algorithmically makes predictions based on total miles, projected miles per hour, past trips by other Google Maps users, road construction, driving conditions, etc.

You ask your friends to provide a range of how long they think it will take you, specifically, to make the trip. They (plus Google) come back with this:

-

Google Maps: 4 hours, 8 minutes

-

Fred: 3.5 – 4.5 hours

-

Mary: 3 – 5 hours

-

Sanjay: 4 – 5 hours

-

Steven: 7 – 8 hours

Three of the four experts plus an algorithm roughly agree about the drive time. But, what’s up with Steven’s estimate? Why does one expert disagree with the group?

A Common Occurrence

Some variability between experts is always expected and even desired. One expert, or a minority of experts, with a divergent opinion, is a fairly common occurrence in any risk analysis project that involves human judgment. Anecdotally, I’d say about one out of every five risk analyses I perform has this issue. There isn’t one single way to deal with it. The risk analyst needs to get to the root cause of the divergence and make a judgment call.

I have two sources of inspiration for this post. First, Carol Williams recently wrote a blog post titled Can We Trust the Experts During Risk Assessments? in her blog, ERM Insights, about the problem of differing opinions from experts when eliciting estimations. Second is the new book Noise by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R. Sunstein, covering the topic from a macro level. They define noise as “unwanted variability in judgments.”

Both sources inspired and caused me to think about how, when, and where I see variability in expert judgment and what I do to deal with it. I’ve identified four reasons this may happen and how to best respond.

Cause #1: Uncalibrated Experts

Image credit: AG Pic

All measurement tools need to be calibrated, meaning the instrument is configured to provide accurate results within an acceptable margin of error. The human mind, being a tool of measurement, also needs to be calibrated.

Calibration doesn’t make human expert judgment less wrong. Calibration training helps experts frame their knowledge and available data into a debiased estimate. The estimates of calibrated experts outperform uncalibrated experts because they have the training, practice, and learning about their inherent personal biases to provide estimates with a higher degree of accuracy.

Calibration is one of the first things I look for if an individual’s estimations are wildly different from the group: have they gone through estimation and calibration training?

Solution

Put the expert through calibration training – self-study or formalized. There are many online sources to choose from, including Doug Hubbard’s course and the Good Judgement Project’s training.

Cause #2: Simple misunderstanding

Some experts simply misunderstand the purpose, scope of the analysis, research, or assumptions.

I was once holding a risk forecasting workshop, and I asked the group to forecast how many complete power outages we should expect our Phoenix datacenter to have in the next ten years, given that we’ve experienced two in the last decade. All of the forecasts were about the same – between zero and three. One expert came back with 6-8, which is quite different from everyone else. After a brief conversation, it turned out he misheard the question. He thought I was asking for a forecast on outages on all datacenters worldwide (over 40) instead of just the one in Phoenix. Maybe he was multitasking during the meeting. We aligned on the question, and his new estimate was about the same as the larger group.

You can provide the same data to a large group of people, and it’s always possible that one or a few people will interpret it differently. If I aggregated this person’s estimation into my analysis without following up, it would have changed the result and produced a report based on faulty assumptions.

Solution

Follow up with the expert and review their understanding of the request. Probe and see if you can find if and where they have misunderstood something. If this is the case, provide extra data and context and adjust the original estimate.

Cause #3: Different worldview

Your expert may view the future – and the problem – differently than the group. Consider the field of climate science as a relevant example.

Climate science forecasting partially relies on expert judgment and collecting probability estimates from scientists. The vast majority – 97% – of active climate scientists agree that humans are causing global warming. 3% do not. This is an example of a different worldview. Many experts have looked at the same data, same assumptions, same questions, and a small subgroup has a different opinion than the majority.

Some examples in technology risk:

-

A minority of security experts believe that data breaches at a typical US-based company aren’t as frequent or as damaging as generally thought.

-

A small but sizable group of security experts assert that security awareness training has very little influence on the frequency of security incidents. (I’m one of them).

-

Some security risk analysts believe the threat of state-sponsored attacks to the typical US company is vastly overstated.

Solution

Let the expert challenge your assumptions. Is there an opportunity to revise your assumptions, data, or analysis? Depending on the analysis and the level of disagreement, you may want to consider multiple risk assessments that show the difference in opinions. Other times, it may be more appropriate to go with the majority opinion but include information on the differing opinion in the final write-up.

Keep in mind this quote:

“Science is not a matter of majority vote. Sometimes it is the minority outlier who ultimately turns out to have been correct. Ignoring that fact can lead to results that do not serve the needs of decision makers.”

– M. Granger Morgan

Cause #4: The expert knows something that no one else knows

It’s always possible that the expert that has a vastly different opinion than everyone else knows something no one else knows.

I once held a risk workshop with a group of experts forecasting the probable frequency of SQL Injection attacks on a particular build of servers. Using data, such as historical compromise rates, industry data, vuln scans, and penetration test reports, all the participants provided a forecast that were generally the same. Except for one guy.

He provided an estimate that forecasted SQL Injection at about 4x the rate as everyone else. I followed up with him, and he told me that the person responsible for patching those systems quit three weeks ago, no one is doing his job currently, and a SQL Injection 0-day is being actively used in the wild! The other experts were not aware of these facts. Oops!

If I ignored or included his estimates as-is, this valuable piece of information would have been lost.

Solution

Always follow up! If someone has extra data that no one else has, this is an excellent opportunity to share it with the larger group and get a better forecast.

Conclusion

Let’s go back to my Vegas trip for a moment. What could be the cause of Steven’s divergent estimate?

-

Not calibrated: He has the basic data but lacks the training on articulating that into a usable range.

-

Simple misunderstanding: “Oh, I forgot you moved from San Jose to Los Angeles last year. When you asked me how long it would take to drive to Vegas, I incorrectly gave you the San Jose > Vegas estimate.” Different assumptions!

-

Different worldview: This Steven drives under the speed limit and only in the slow lane. He prefers stopping for meals on schedule and eats at sit-down restaurants – never a drive-through. He approaches driving and road trips differently than you do, and his estimates reflect this view.

-

Knows something that the other experts do not know: This Steven remembered that you are bringing your four kids that need to stop often for food, bathroom, and stretch breaks.

In all cases, a little bit of extra detective work finds the root cause of the divergent opinion.

I hope this gives a few good ideas on how to solve this fairly common issue. Did I miss any causes or solutions? Let me know in the comments below.

Further reading

-

Aggregating Expert Opinion in Risk Analysis: An Overview of Methods

-

Aggregating Expert Opinion: Simple Averaging Method in Excel

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Blog - Tony Martin-Vegue authored by Tony MartinVegue. Read the original post at: https://www.tonym-v.com/blog/2021/6/30/when-the-experts-disagree-in-risk-analysis