Assange indicted for breaking a password

In today’s news, after 9 years holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy, Julian Assange has finally been arrested. The US DoJ accuses Assange for trying to break a password. I thought I’d write up a technical explainer what this means.

According to the US DoJ’s press release:

Julian P. Assange, 47, the founder of WikiLeaks, was arrested today in the United Kingdom pursuant to the U.S./UK Extradition Treaty, in connection with a federal charge of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion for agreeing to break a password to a classified U.S. government computer.

It seems the indictment is based on already public information that came out during Manning’s trial, namely this log of chats between Assange and Manning, specifically this section where Assange appears to agree to break a password:

What this says is that Manning hacked a DoD computer and found the hash “80c11049faebf441d524fb3c4cd5351c” and asked Assange to crack it. Assange appears to agree.

So what is a “hash”, what can Assange do with it, and how did Manning grab it?

Computers store passwords in an encrypted (sic) form called a “one way hash”. Since it’s “one way”, it can never be decrypted. However, each time you log into a computer, it again performs the one way hash on what you typed in, and compares it with the stored version to see if they match. Thus, a computer can verify you’ve entered the right password, without knowing the password itself, or storing it in a form hackers can easily grab. Hackers can only steal the encrypted form, the hash.

When they get the hash, while it can’t be decrypted, hackers can keep guessing passwords, performing the one way algorithm on them, and see if they match. With an average desktop computer, they can test a billion guesses per second. This may seem like a lot, but if you’ve chosen a sufficiently long and complex password (more than 12 characters with letters, numbers, and punctuation), then hackers can’t guess them.

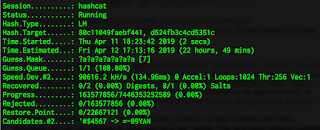

It’s unclear what format this password is in, whether “NT” or “NTLM”. Using my notebook computer, I could attempt to crack the NT format using the hashcat password crack with the following command:

hashcat -m 3000 -a 3 80c11049faebf441d524fb3c4cd5351c ?a?a?a?a?a?a?a

As this image shows, it’ll take about 22 hours on my laptop to crack this. However, this doesn’t succeed, so it seems that this isn’t in the NT format. Unlike other password formats, the “NT” format can only be 7 characters in length, so we can completely crack it.

Instead of brute-force trying all possible combinations of characters each time we have a new password, we could do the huge calculation just once and save all the “password -> hash” combinations to a disk drive. Then, each time we get a new hash from hacking a computer, we can just do a simple lookup. However, this won’t work in practice, because the number of combinations is just too large — even if we used all the disk drives in the world to store the results, it still wouldn’t be enough.

But there’s a neat trick called “Rainbow Tables” that does a little bit of both, using both storage and computation. If cracking a password would be of 64 bits of difficulty, you can instead use 32 bits of difficulty for storage (storing 4 billion data points) and do 32 bits worth of computation (doing 4 billion password hashes). In other words, while doing 64 bits of difficulty is prohibitively difficult, 32 bits of both storage and computation means it’ll take up a few gigabytes of space and require only a few seconds of computation — an easy problem to solve.

That’s what Assange promises, that they have the Rainbow Tables and expertise needed to crack the password.

However, even then, the Rainbow Tables aren’t complete. While the “NT” algorithm has a limit of 7 characters, the “NTLM” has no real limit. Building the tables in the first place takes a lot of work. As far as I know, we don’t have NTLM Rainbow Tables for passwords larger than 9 complex characters (upper, lower, digits, punctuation, etc.).

I don’t know the password requirements that were in effect back then 2010, but there’s a good chance it was on the order of 12 characters including digits and punctuation. Therefore, Rainbow Cracking wouldn’t have been possible.

If we can’t brute-force all combinations of a 12 character password, or use Rainbow Tables, how can we crack it? The answer would be “dictionary attacks”. Over the years, we’ve acquired real-world examples of over a billion passwords people have used in real accounts. We can simply try all those, regardless of length. We can also “mutate” this dictionary, such as adding numbers on the end. This requires testing trillions of combinations, but with hardware that can try a billion combinations per second, it’s not too onerous.

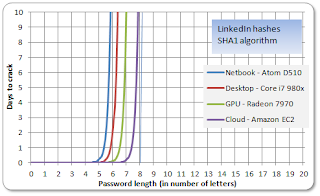

But there’s still a limit to how effective we can be at password cracking. As I explain in other posts, the problem is exponential. Each additional character increases the difficult by around 100 times. In other words, if you can brute-force all combinations of a password of a certain length in a week, then adding one character to the length means you’ll take now 100 weeks, or two years. That’s why even nation state spies, like the NSA, with billions of dollars of hardware, may not be able to crack this password.

|

| LinkedIn passwords, how long it takes a laptop or nation state to crack |

Now let’s tackle the question of how Manning got the hash in the first place. It appears the issue is that Manning wanted to logon as a different user, hiding her tracks. She therefore wanted to grab the other person’s password hash, crack the password, then use it to logon, with all her nefarious activities now associated with the wrong user.

She can’t simply access the other user account. That’s what operating systems do, prevent you from accessing other parts of the disk that don’t belong to you.

To get around this, she booted the computer with a different operating system from a CD drive, with some sort of Linux distro. From that operating system, she had full access to the drive. As the chatlog reveals, she did the standard thing that all hackers do, copy over the SAM file, then dump the hashes from it. Here is an explanation from 2010 that roughly describes exactly what she did.

The term “Linux” was trending today on Twitter by people upset by the way the indictment seemed to disparage it as some sort of evil cybercrime tool, but I don’t read it that way. The evil cybercrime act the indictment refers to use is booting another operating system from a CD. It no more disparages Linux than it disparages CDs. It’s the booting an alternate operating system and stealing the SAM file that demonstrates criminality, not CDs or Linux.

Note that stealing another account’s password apparently wasn’t about being able to steal more documents. This can become an important factor later on when appealing the case.

The documents weren’t on the computer, but on the network. Thus, while booting Linux from a CD would allow full access to all the documents on the local desktop computer, it still wouldn’t allow access to the server.

Apparently, it was just another analyst’s account Manning was trying to hijack, who had no more permissions on the network than she did. Thus, she wouldn’t have been accessing any files she wasn’t already authorized to access.

Therefore, as CFAA/4thA expert Orin Kerr tweets, there may not have been a CFAA violation:

Second, it’s based on a relatively aggressive (and somewhat controversial) view of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act — that accessing files in violation of an order on classified materials is an unauthorized access.— Orin Kerr (@OrinKerr) April 11, 2019

Conclusion

*** This is a Security Bloggers Network syndicated blog from Errata Security authored by Robert Graham. Read the original post at: https://blog.erratasec.com/2019/04/assange-indicted-for-breaking-password.html